More essential reading lists

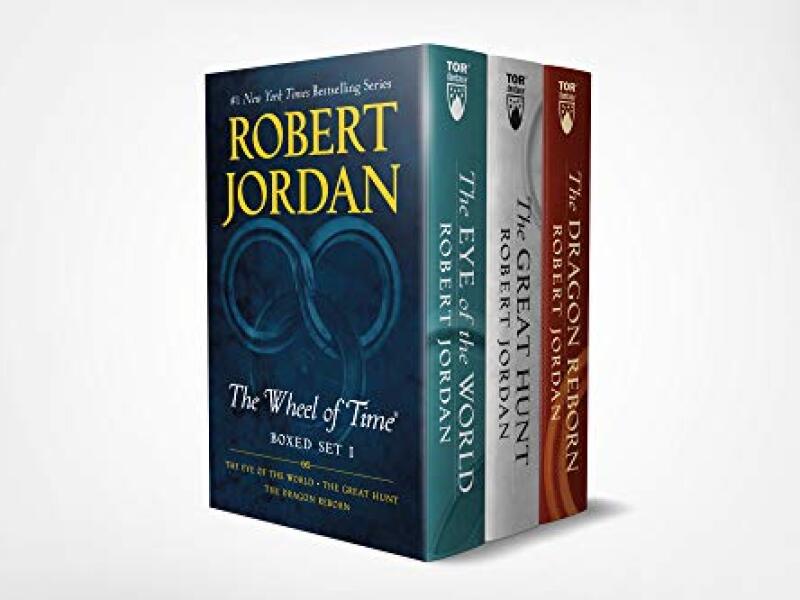

Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time high fantasy series is epic in more ways than one. There are 14 novels where Jordan creates an imaginary magical world in immense detail and introduces thousands of good and evil characters.

1 Min Read

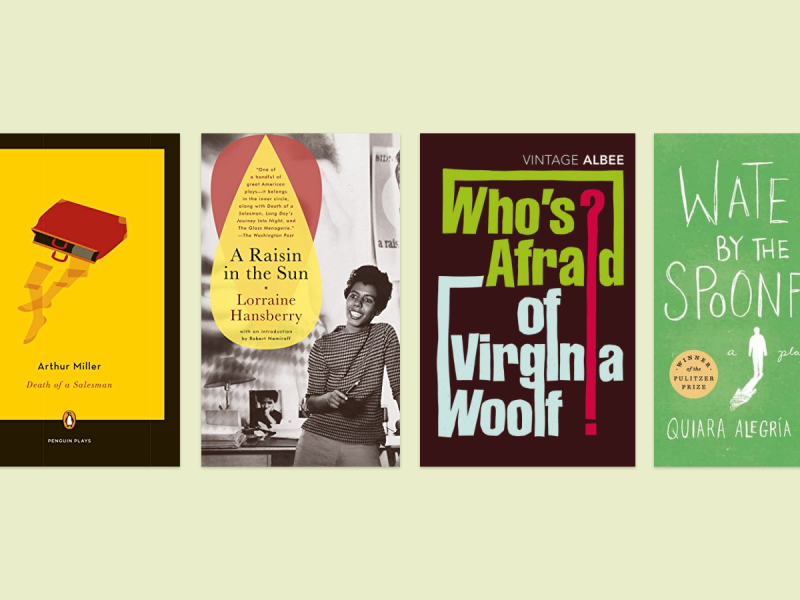

Written for the stage but just as good a read as any novel, a plays book is a book that contains the script of one or more dramatic plays. This list of 15 plays books includes well-known classics like A Street car Named Desire and Twelve Angry Men alongside modern award-winners including Water by the Spoonful and Wit.

1 Min Read

The top fiction and non fiction books of 2021. Our top picks for the best books of the year include Pulitzer and Nobel Prize winners, New York Times bestsellers, and many titles shortlisted for the year's big book awards.

1 Min Read