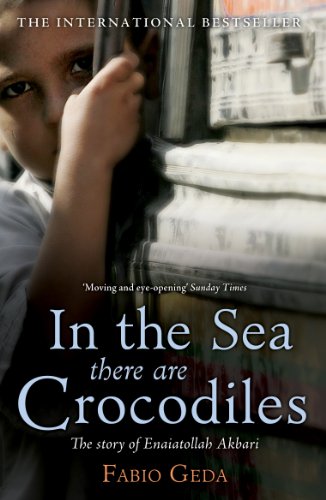

Items related to In the Sea there are Crocodiles

One night before putting him to bed, Enaiatollah's mother tells him three things: don't use drugs or weapons, don't cheat, don't steal. The next day he wakes up to find she isn't there. Ten-year-old Enaiatollah is left alone at the border of Pakistan to fend for himself. In a book that takes a true story and shapes it into a beautiful piece of fiction, Italian novelist Fabio Geda describes Enaiatollah's remarkable five-year journey from Afghanistan to Italy where he finally managed to claim political asylum aged fifteen. His ordeal took him through Iran, Turkey and Greece, working on building sites in order to pay people-traffickers, and enduring the physical misery of dangerous border crossings squeezed into the false bottoms of lorries or trekking across inhospitable mountains. A series of almost implausible strokes of fortune enabled him to get to Turin, find help from an Italian family and meet Fabio Geda, with whom he became friends. The result of their friendship is this unique book in which Enaiatollah's engaging, moving voice is brilliantly captured by Geda's subtly simple storytelling. In Geda's hands, Enaiatollah's journey becomes a universal story of stoicism in the face of fear, and the search for a place where life is liveable.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

I met Enaiatollah Akbari at a book presentation where I was speaking about my first novel, the story of a Romanian boy’s life as an immigrant in Italy. Enaiatollah came up to me and said he’d had a similar experience. We got talking. And we didn’t stop. I never tired of listening to his experiences, and he didn’t tire of dredging them from his memory. After we’d known each other for a while, he asked me if I would write his story down, so that people who had suffered similar things could know they were not alone, and so that others might understand them better.

This book is therefore based on a true story. But, of course, Enaiatollah didn’t remember it all perfectly. Together we painstakingly reconstructed his journey, looking at maps, consulting Google, trying to create a chronology for his fragmented memories. I have tried to be as true to his voice as possible, retelling the story exactly as he told it. But for all that, this book must be considered fiction, since it is the recreation of Enaiatollah’s experience – a recreation that has allowed him to take possession of his own story.

Fabio Geda, Turin 2010

Afghanistan

The thing is, I really wasn’t expecting her to go. Because when you’re ten years old and getting ready for bed, on a night that’s just like any other night, no darker or starrier or more silent or more full of smells than usual, with the familiar sound of the muezzins calling the faithful to prayer from the tops of the minarets just like anywhere else . . . no, when you’re ten years old--I say ten, although I’m not entirely sure when I was born, because there’s no registry office or anything like that in Ghazni province--like I said, when you’re ten years old, and your mother, before putting you to bed, takes your head and holds it against her breast for a long time, longer than usual, and says, There are three things you must never do in life, Enaiat jan, for any reason . . . The first is use drugs. Some of them taste good and smell good and they whisper in your ear that they’ll make you feel better than you could ever feel without them. Don’t believe them. Promise me you won’t do it.

I promise.

The second is use weapons. Even if someone hurts your feelings or damages your memories, or insults God, the earth or men, promise me you’ll never pick up a gun, or a knife, or a stone, or even the wooden ladle we use for making qhorma palaw, if that ladle can be used to hurt someone. Promise.

I promise.

The third is cheat or steal. What’s yours belongs to you, what isn’t doesn’t. You can earn the money you need by working, even if the work is hard. You must never cheat anyone, Enaiat jan, all right? You must be hospitable and tolerant to everyone. Promise me you’ll do that.

I promise.

Anyway, even when your mother says things like that and then, still stroking your neck, looks up at the window and starts talking about dreams, dreams like the moon, which at night is so bright you can see to eat by it, and about wishes--how you must always have a wish in front of your eyes, like a donkey with a carrot, and how it’s in trying to satisfy our wishes that we find the strength to pick ourselves up, and if you hold a wish up high, any wish, just in front of your forehead, then life will always be worth living--well, even when your mother, as she helps you get to sleep, says all these things in a strange, low voice as warming as embers, and fills the silence with words, this woman who’s always been so sharp, so quick-witted in dealing with life . . . even at a time like that, it doesn’t occur to you that what she’s really saying is, Khoda negahdar, goodbye.

Just like that.

When I opened my eyes in the morning, I had a good stretch to wake myself up, then reached over to my right, feeling for the comforting presence of my mother’s body. The reassuring smell of her skin always said to me, Wake up, get out of bed, come on . . . But my hand felt nothing, only the white cotton cover between my fingers. I pulled it toward me. I turned over, with my eyes wide open. I propped myself on my elbows and tried calling out, Mother. But she didn’t reply and no one replied in her place. She wasn’t on the mattress, she wasn’t in the room where we had slept, which was still warm with bodies tossing and turning in the half-light, she wasn’t in the doorway, she wasn’t at the window looking out at the street filled with cars and carts and bikes, she wasn’t next to the water jars or in the smokers’ corner talking to someone, as she had often been during those three days.

From outside came the din of Quetta, which is much, much noisier than my little village in Ghazni, that strip of land, houses and streams that I come from, the most beautiful place in the world (and I’m not just boasting, it’s true).

Little or big.

It didn’t occur to me that the reason for all that din might be because we were in a big city. I thought it was just one of the normal differences between countries, like different ways of seasoning meat. I thought the sound of Pakistan was simply different from the sound of Afghanistan, and that every country had its own sound, which depended on a whole lot of things, like what people ate and how they moved around.

Mother, I called.

No answer. So I got out from under the covers, put my shoes on, rubbed my eyes and went to find the owner of the place to ask if he’d seen her, because three days earlier, as soon as we arrived, he’d told us that no one went in or out without him noticing, which seemed odd to me, since I assumed that even he needed to sleep from time to time.

The sun cut the entrance of the samavat Qgazi in two. Samavat means “hotel.” In that part of the world, they actually call those places hotels, but they’re nothing like what you think of as a hotel, Fabio. The samavat Qgazi wasn’t so much a hotel as a warehouse for bodies and souls, a kind of left-luggage office you cram into and then wait to be packed up and sent off to Iran or Afghanistan or wherever, a place to make contact with people traffickers.

We had been in the samavat for three days, never going out, me playing among the cushions, Mother talking to groups of women with children, some with whole families, people she seemed to trust.

I remember that, all the time we were in Quetta, my mother kept her face and body bundled up inside a burqa. In our house in Nava, with my aunt or with her friends, she never wore a burqa. I didn’t even know she had one. The first time I saw her put it on, at the border, I asked her why and she said with a smile, It’s a game, Enaiat, come inside. She lifted a flap of the garment, and I slipped between her legs and under the blue fabric. It was like diving into a swimming pool, and I held my breath, even though I wasn’t swimming.

Covering my eyes with my hand because of the light, I walked up to the owner, kaka Rahim, and apologized for bothering him. I asked about my mother, if by any chance he’d seen her go out, because nobody went in or out without him noticing, right?

Kaka Rahim was smoking a cigarette and reading a newspaper written in English, some of it in red, some in black, without pictures. He had long lashes and his cheeks were covered with a fine down like those furry peaches you sometimes get, and next to the newspaper, on the table at the entrance, was a plate containing a pile of apricot stones, along with three succulent-looking, orange-colored fruits, still uneaten, and a handful of mulberries.

There’s a lot of fruit in Quetta, Mother had told me. She had said it to entice me, because I love fruit. In Pashtun, Quetta means “fortified trading center” or something like that, a place where goods are exchanged: objects, lives. Quetta is the capital of Baluchistan: the fruit garden of Pakistan.

Without turning around, kaka Rahim blew smoke into the sun. Yes, he replied, I saw her.

I smiled. Where did she go, kaka Rahim? Can you tell me?

Away.

Away where?

Away.

When will she be back?

She’s not coming back.

She’s not coming back?

No.

What do you mean? Kaka Rahim, what do you mean, she’s not coming back?

She’s not coming back.

At that point I ran out of questions. There must have been others I could have asked, but I didn’t know what they were. I stood there in silence looking at the down on kaka Rahim’s cheeks, but without really seeing it.

It was kaka Rahim who spoke next. She told me to tell you something, he said.

What?

Khoda negahdar.

Is that all?

No, there was something else.

What, kaka Rahim?

She said not to do the three things she told you not to do.

Born in Turin in 1972, Fabio Geda is an Italian novelist who works with children in difficulties. He writes for several Italian magazines and newspapers, and teaches creative writing in the most famous Italian school of storytelling (Scuola Holden, in Turin). This is his first book to be translated into English.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

I met Enaiatollah Akbari at a book presentation where I was speaking about my first novel, the story of a Romanian boy’s life as an immigrant in Italy. Enaiatollah came up to me and said he’d had a similar experience. We got talking. And we didn’t stop. I never tired of listening to his experiences, and he didn’t tire of dredging them from his memory. After we’d known each other for a while, he asked me if I would write his story down, so that people who had suffered similar things could know they were not alone, and so that others might understand them better.

This book is therefore based on a true story. But, of course, Enaiatollah didn’t remember it all perfectly. Together we painstakingly reconstructed his journey, looking at maps, consulting Google, trying to create a chronology for his fragmented memories. I have tried to be as true to his voice as possible, retelling the story exactly as he told it. But for all that, this book must be considered fiction, since it is the recreation of Enaiatollah’s experience – a recreation that has allowed him to take possession of his own story.

Fabio Geda, Turin 2010

Afghanistan

The thing is, I really wasn’t expecting her to go. Because when you’re ten years old and getting ready for bed, on a night that’s just like any other night, no darker or starrier or more silent or more full of smells than usual, with the familiar sound of the muezzins calling the faithful to prayer from the tops of the minarets just like anywhere else . . . no, when you’re ten years old--I say ten, although I’m not entirely sure when I was born, because there’s no registry office or anything like that in Ghazni province--like I said, when you’re ten years old, and your mother, before putting you to bed, takes your head and holds it against her breast for a long time, longer than usual, and says, There are three things you must never do in life, Enaiat jan, for any reason . . . The first is use drugs. Some of them taste good and smell good and they whisper in your ear that they’ll make you feel better than you could ever feel without them. Don’t believe them. Promise me you won’t do it.

I promise.

The second is use weapons. Even if someone hurts your feelings or damages your memories, or insults God, the earth or men, promise me you’ll never pick up a gun, or a knife, or a stone, or even the wooden ladle we use for making qhorma palaw, if that ladle can be used to hurt someone. Promise.

I promise.

The third is cheat or steal. What’s yours belongs to you, what isn’t doesn’t. You can earn the money you need by working, even if the work is hard. You must never cheat anyone, Enaiat jan, all right? You must be hospitable and tolerant to everyone. Promise me you’ll do that.

I promise.

Anyway, even when your mother says things like that and then, still stroking your neck, looks up at the window and starts talking about dreams, dreams like the moon, which at night is so bright you can see to eat by it, and about wishes--how you must always have a wish in front of your eyes, like a donkey with a carrot, and how it’s in trying to satisfy our wishes that we find the strength to pick ourselves up, and if you hold a wish up high, any wish, just in front of your forehead, then life will always be worth living--well, even when your mother, as she helps you get to sleep, says all these things in a strange, low voice as warming as embers, and fills the silence with words, this woman who’s always been so sharp, so quick-witted in dealing with life . . . even at a time like that, it doesn’t occur to you that what she’s really saying is, Khoda negahdar, goodbye.

Just like that.

When I opened my eyes in the morning, I had a good stretch to wake myself up, then reached over to my right, feeling for the comforting presence of my mother’s body. The reassuring smell of her skin always said to me, Wake up, get out of bed, come on . . . But my hand felt nothing, only the white cotton cover between my fingers. I pulled it toward me. I turned over, with my eyes wide open. I propped myself on my elbows and tried calling out, Mother. But she didn’t reply and no one replied in her place. She wasn’t on the mattress, she wasn’t in the room where we had slept, which was still warm with bodies tossing and turning in the half-light, she wasn’t in the doorway, she wasn’t at the window looking out at the street filled with cars and carts and bikes, she wasn’t next to the water jars or in the smokers’ corner talking to someone, as she had often been during those three days.

From outside came the din of Quetta, which is much, much noisier than my little village in Ghazni, that strip of land, houses and streams that I come from, the most beautiful place in the world (and I’m not just boasting, it’s true).

Little or big.

It didn’t occur to me that the reason for all that din might be because we were in a big city. I thought it was just one of the normal differences between countries, like different ways of seasoning meat. I thought the sound of Pakistan was simply different from the sound of Afghanistan, and that every country had its own sound, which depended on a whole lot of things, like what people ate and how they moved around.

Mother, I called.

No answer. So I got out from under the covers, put my shoes on, rubbed my eyes and went to find the owner of the place to ask if he’d seen her, because three days earlier, as soon as we arrived, he’d told us that no one went in or out without him noticing, which seemed odd to me, since I assumed that even he needed to sleep from time to time.

The sun cut the entrance of the samavat Qgazi in two. Samavat means “hotel.” In that part of the world, they actually call those places hotels, but they’re nothing like what you think of as a hotel, Fabio. The samavat Qgazi wasn’t so much a hotel as a warehouse for bodies and souls, a kind of left-luggage office you cram into and then wait to be packed up and sent off to Iran or Afghanistan or wherever, a place to make contact with people traffickers.

We had been in the samavat for three days, never going out, me playing among the cushions, Mother talking to groups of women with children, some with whole families, people she seemed to trust.

I remember that, all the time we were in Quetta, my mother kept her face and body bundled up inside a burqa. In our house in Nava, with my aunt or with her friends, she never wore a burqa. I didn’t even know she had one. The first time I saw her put it on, at the border, I asked her why and she said with a smile, It’s a game, Enaiat, come inside. She lifted a flap of the garment, and I slipped between her legs and under the blue fabric. It was like diving into a swimming pool, and I held my breath, even though I wasn’t swimming.

Covering my eyes with my hand because of the light, I walked up to the owner, kaka Rahim, and apologized for bothering him. I asked about my mother, if by any chance he’d seen her go out, because nobody went in or out without him noticing, right?

Kaka Rahim was smoking a cigarette and reading a newspaper written in English, some of it in red, some in black, without pictures. He had long lashes and his cheeks were covered with a fine down like those furry peaches you sometimes get, and next to the newspaper, on the table at the entrance, was a plate containing a pile of apricot stones, along with three succulent-looking, orange-colored fruits, still uneaten, and a handful of mulberries.

There’s a lot of fruit in Quetta, Mother had told me. She had said it to entice me, because I love fruit. In Pashtun, Quetta means “fortified trading center” or something like that, a place where goods are exchanged: objects, lives. Quetta is the capital of Baluchistan: the fruit garden of Pakistan.

Without turning around, kaka Rahim blew smoke into the sun. Yes, he replied, I saw her.

I smiled. Where did she go, kaka Rahim? Can you tell me?

Away.

Away where?

Away.

When will she be back?

She’s not coming back.

She’s not coming back?

No.

What do you mean? Kaka Rahim, what do you mean, she’s not coming back?

She’s not coming back.

At that point I ran out of questions. There must have been others I could have asked, but I didn’t know what they were. I stood there in silence looking at the down on kaka Rahim’s cheeks, but without really seeing it.

It was kaka Rahim who spoke next. She told me to tell you something, he said.

What?

Khoda negahdar.

Is that all?

No, there was something else.

What, kaka Rahim?

She said not to do the three things she told you not to do.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherRandom House

- Publication date2015

- ISBN 10 1848531389

- ISBN 13 9781848531383

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages224

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 6.53

Shipping:

US$ 27.95

From United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

In the Sea there are Crocodiles

Seller:

Rating

Book Description paperback. Condition: New. Shipped from the UK within 2 business days of order being placed. Seller Inventory # mon0000290161

Buy New

US$ 6.53

Convert currency