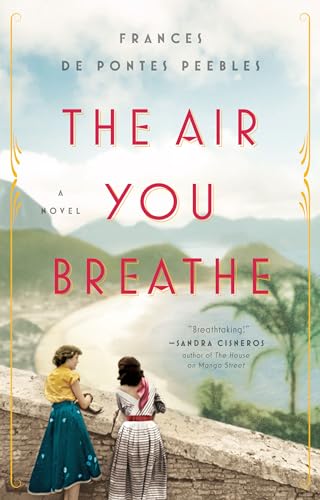

Items related to The Air You Breathe: A Novel

"Echoes of Elena Ferrante resound in this sumptuous saga."--O, The Oprah Magazine

"Enveloping...Peebles understands the shifting currents of female friendship, and she writes so vividly about samba that you close the book certain its heroine's voices must exist beyond the page." -People

The story of an intense female friendship fueled by affection, envy and pride--and each woman's fear that she would be nothing without the other.

Some friendships, like romance, have the feeling of fate.

Skinny, nine-year-old orphaned Dores is working in the kitchen of a sugar plantation in 1930s Brazil when in walks a girl who changes everything. Graça, the spoiled daughter of a wealthy sugar baron, is clever, well fed, pretty, and thrillingly ill behaved. Born to wildly different worlds, Dores and Graça quickly bond over shared mischief, and then, on a deeper level, over music.

One has a voice like a songbird; the other feels melodies in her soul and composes lyrics to match. Music will become their shared passion, the source of their partnership and their rivalry, and for each, the only way out of the life to which each was born. But only one of the two is destined to be a star. Their intimate, volatile bond will determine each of their fortunes--and haunt their memories.

Traveling from Brazil's inland sugar plantations to the rowdy streets of Rio de Janeiro's famous Lapa neighborhood, from Los Angeles during the Golden Age of Hollywood back to the irresistible drumbeat of home, The Air You Breathe unfurls a moving portrait of a lifelong friendship--its unparalleled rewards and lasting losses--and considers what we owe to the relationships that shape our lives.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Time is short and the water is rising.

This is what one of Sofia Salvador’s directors—I can’t recall his name—used to shout before he’d start filming. Each time he said it, I imagined all of us in a fishbowl, our hands sliding frantically along the glass sides as water crept above our necks, our noses, our eyes.

I fall asleep listening to our old records and wake with my mouth dry, my tongue as rough as a cat’s. I pull the handle of my La-Z-Boy and, with a jolt, am sitting upright. A pile of photos rests in my lap.

I own the most famous photograph of Sofia Salvador—the Brazilian Bombshell, the Fruity Cutie Girl, the fast-talking, eye-popping nymph with her glittering costumes and pixie-cut hair who, depending on your age and nationality, is either a joke, an icon of camp, a victim, a traitor, a great innovator, or even, as one researcher anointed her, “an object of serious study of Hollywood’s Latinas.” (Is that what they’re calling us now?) I bought the original photo and its negative at auction, paying much more than they were worth. Money isn’t an issue for me these days; I’m filthy rich and am not ashamed to say so. When I was young, musicians had to pretend that success and money didn’t matter. Ambition, in a sambista and especially in a woman, was seen as an unforgivable fault.

In the photo, taken in 1942, Sofia Salvador wears the pixie cut she made famous. Her eyes are wide. Her lips are parted. Her tongue flicks the roof of her mouth; it is unclear if she is singing or screaming. Earrings made to resemble life-sized hummingbirds—their jeweled eyes glinting, their golden beaks sharp—dangle from her ears. She was vain about her lobes, worried they would sag under the weight of her array of earrings, each one more fantastical than the next. She was vain about everything, really; she had to be.

In the photograph she wears a gold choker, wrapped twice around her neck. Below it are strand upon strand of fake pearls, each one as large as an eyeball. Then there are the bracelets—bands of coral and gold—taking up most of her forearms. At the end of each day, when I’d take those necklaces and bracelets off her and she stopped being Sofia Salvador (for a moment, at least), Graça flapped her arms and said, “I feel so light. I could fly away!”

Graça drew Sofia’s dark eyebrows arched so high she always looked surprised. The mouth—that famous red mouth—was what took her the longest to produce. She lined beyond her lips so that, like everything else, it was an exaggeration of the real thing. Who was the real thing? By the end of her short life, even Graça had trouble answering this question.

The picture was taken for Life magazine. The photographer stood Graça against a white backdrop. “Pretend you’re singing,” he ordered. “Why pretend?” Graça replied.

“I thought that’s all you knew how to do,” the photographer shot back. He was famous and believed his fame gave him the right to be nasty.

Graça stared. She was very tired. We always were, even me, who signed Sofia Salvador’s name to hundreds of glossy photos while Graça and the Blue Moon boys endured eighteen-hour days of filming, costume fittings, screen tests, dance rehearsals, and publicity shoots for whatever her latest movie musical was. It could have been worse; we could have been starving like in the old days. But at least in the old days we played real music, together.

“Then I will pretend to respect you,” Graça said to that fool photographer. Then she opened her mouth and sang. People remember the haircut, the enormous earrings, the sequined skirts, the accent, but they forget her voice. When she sang for that photographer, his camera nearly fell from his hands.

I listen to her records—only our early recordings, when she sang Vinicius’s and my songs—and it is as if she is still seventeen and sitting beside me. Graça, with all of her willfulness, her humor, her petty resistances, her pluck, her complete selfishness. This is how I want her, if only for the span of a three-minute song.

When the song ends, I’m exhausted and whimpering. I imagine her here, nudging me, bringing me back to my senses.

Why the hell are you upset, Dor? Graça chides. At least you’re still around.

Her voice is so clear, I have to remind myself she isn’t real. I have known Graça longer in my imagination than in real life.

Who wants real life? Graça asks, laughing at me. (She is always laughing at someone.)

I shake my head. After all this time—ninety-five years, to be exact— I still do not know the answer.

My current life is a dull jumble of walks along the beach chaperoned by a nurse; trips to the grocery store; afternoons in my office; evenings listening to records; tedious hours spent tolerating a steady stream of physical therapists and doctors with their proclamations and humorless devotion. I live in a vast house surrounded by paid help. Once, long ago, I wished for such ease.

Be careful what you wish for, Dor.

It’s too late to be careful now, amor.

Now, I wish for the early, chaotic part of my life—those first thirty or so years—to return to me, even with its cruelty, its sacrifice, its missteps, its misdeeds. My misdeeds. If I could hear my life—if I could put it on a turntable like a worn-out LP—I’d hear samba. Not the boisterous kind they play during Carnaval. Not one of those silly marchinhas, as short-lived and vapid as bubbles. And not the soft-spoken, romantic sort, either. No. Mine would be the kind of samba you’d find in a roda: the kind we played in a circle after work and a few stiff drinks. It begins quite dire-sounding, perhaps with the lonely moan of a cuíca. Then, ever so slowly, others join the roda—voices, guitars, a tamborim drum, the scratch of a reco-reco—and the song begins to claw its way out of its lowly beginning and into something fuller, thicker, darker. It has all of the elements of a true samba (though not necessarily a great one). There is lament, humor, rebelliousness, lust, ambition, regret. And love. There is that, too. It is all improvisation, so if there are mistakes I must move past them and keep playing. Beneath it all, there is the ostinato—the main groove that never varies, never wavers. It keeps its stubborn pace; the beat that’s always there. And here I am: the only one left in the circle, conjuring voices I have not heard in decades, listening to a chorus of arguments I should never have made. I have tried not to hear this song in full. I have tried to blot it out with drink and time and indifference. But it remains in my head, and will not stop until I recall all of its words. Until I sing it out loud, from beginning to end.

THE SWEET RIVER

Share this bottle with me,

share this song.

The years have hardened my heart.

Drink will loosen my tongue.

Come, walk with me,

to the places I once loved.

Man made the fire

to burn the fields of cane.

God made music

to take away my pain.

I come from a land

where sugar is king and the river is sweet.

They say a woman drowned there,

her ghost haunts the deep.

Sit beside me now, at the riverbank

hear my voice, loud and strong.

Wade into these sweet waters with me,

let me open your heart with a song.

Now we’re both pulled under, friend,

singing the same refrain:

Dive back, again, to the place you once loved

and you’ll find it’s never the same.

Man made the fire

to burn the fields of cane. God made music

to take away my pain.

THE SWEET RIVER

It would be better to begin with Graça—with her arrival, with our first meeting. But life isn’t as orderly as a story or a song; it does not always begin and end at compelling points. Even before Graça’s arrival, even as a small child, I sensed that I’d been born into a role that didn’t fit my ambitions, like a stalk of sugarcane crammed into a thimble.

I survived my own birth, a true feat in 1920 if you were born to a dirt-poor mother living on a sugar plantation. The midwife who delivered me told everyone how surprised she was that such a hearty girl could’ve come from my mother’s tired womb. I was her fifth and final child. Most women who worked on the plantation had ten or twelve or even eighteen children, so my mother’s womb was fresher and younger than most. But she was not married and never had been. All of my long-lost brothers and myself—I was the only girl in our lot—had different fathers. This made my mother worse than a puta in many people’s minds, because at least a puta had the sense to charge for her services.

I didn’t dare ask about my mother, afraid of what I might hear and not willing to risk a beating; I was not allowed to ask any questions at all, you see. No one spoke of her, except to insult me. They said I was big-boned, like her. They said I had a temper, like her. They said I was ugly as sin, like her, except I did not have scars covering my arms and face from the cane. She was, for a little while at least, a sugarcane cutter—one of a handful of women who could stomach the work. But the insult that came up the most was the one about her easy way with men. If I didn’t use enough salt to scrub blood from the plantation’s cutting boards, or if I stopped stirring the infernally hot jam on the stove for even a second, or if I was too slow bringing Cook Nena or her staff ingredients from the pantry or garden, I was smacked with a wooden spoon and called “puta’s girl.” So I came to know my mother through all of the things people despised about her, and about me. And I realized, though I could not articulate it clearly as a child, that people hated what they feared, and so I was proud of her.

The midwife took pity on me, being such a healthy baby, and instead of smothering me, or throwing me in the cane for the vultures pick at, or giving me to some plantation owner to raise like a pet or a slave (all common practices back then for girl children without families), she gave me to Nena, the head cook on the Riacho Doce plantation. There were hundreds of cane plantations along the coast of our state of Pernambuco, and Riacho Doce was one of the largest. In good times, when sugar prices were high, Cook Nena led a staff of ten kitchen maids and two houseboys. Nena was as full-breasted as a prize rooster and had hands as large and as lethal as her cast-iron frying pans. The Pimentel family owned Riacho Doce and were the masters of its Great House, but Nena ruled in the kitchen. This is why no one objected when, after the midwife brought me, naked and wailing, to Nena, the cook decided to raise me as her kitchen girl.

Everyone in the Great House—maids, laundresses, stable boys, houseboys—went to Nena’s kitchen to get a look at me. They freely remarked on my rosy skin, my long legs, my perfect feet. A day later, I stopped drinking the goat’s milk Nena gave me in a bottle. Nena visited a local wet nurse and I spat the woman’s teats from my mouth. I was too young to eat manioc porridge but Nena tried to feed it to me anyway. I spat that out, too, and soon turned shriveled and yellow-skinned like an old crone. People said I’d been cursed by the evil eye. Olho mau, they called it, olho gordo. Both are different names for the same bad luck.

Nena went to Old Euclides for help. Euclides was wrinkled, gossipy, and the color of blackstrap scraped from the sugar mill’s vats. He’d worked at R iacho Doce longer than Nena had, first as a stable boy and then as its groundskeeper. He had a donkey who’d given birth and lost her foal but not her milk. Nena took me to the stables and held me straight to that jega’s teat, and I drank. I drank that jega’s milk until I was fat and strong again. My color changed; I was less like a rose and more like that donkey’s tan coat. My hair grew in thick. After that, I was called Jega.

In people’s superstitious and backward minds, the girl I became was inextricably linked to the mother’s milk I’d drunk.

“Jega’s as dumb as an ass,” the houseboys teased.

“Jega’s as stubborn as an ass,” the kitchen maids complained.

“Jega’s as ugly as an ass,” the stable boys said when they felt spiteful.

They all wanted me to believe it. They wanted me to become that Jega. I would never give them that satisfaction.

The Great House sat on a hill. You could stand on its pillared front porch and see nearly all of Riacho Doce’s workings: the main gate, the mill with its blackened smokestack, the horse and donkey stables, the administrator’s house, the carpenter’s shed, the old manioc mill, a small square of pasture and corn, the distillery and warehouses with their thick iron doors. And you could see the brown line of water that gave Riacho Doce its name, although it was much wider than a creek and its waters were not sweet.

Every plantation had a ghost story and ours was no different: a woman had drowned in the creek and lived there still. Some said she was killed by a lover, others said a master, others said she killed herself. They said you could hear her at night, under the waters, singing for her lost love or trying to lure people into the waters and drown them to keep her company; the story depended on whether you believed in the kind ghost or the vengeful one. R iacho Doce’s mothers told their chil- dren this before bed, and it kept them away from the river. I heard the ghost’s story from Nena.

Behind the Great House was an orchard, and behind that the low- roofed slaves’ senzalas that had been converted into servants’ quarters. Nena and I were the only staff allowed to sleep in the Great House it- self, which set us apart from the rest of the servants. This special status didn’t affect Nena as much as it did me. I was Jega—the lowest soul in the strict hierarchy of the Great House—and the maids and houseboys were determined to remind me of this fact. They slapped me, pinched my neck, cursed and spat at me. They thwacked me with wooden spoons and greased the staff doorway with lard to make me slip and fall. They locked me in the foul-smelling outhouse until I kicked my way out. Nena knew about these pranks but didn’t stop them.

“That’s the way a kitchen is,” Nena said. “You’re lucky the boys aren’t trying to get under your skirts. They will soon enough. Better learn to fight them now.”

Nena always issued such warnings to me:

Better keep your head down.

Better stay out of sight.

Better make yourself useful.

If I failed to heed her warnings she beat me with a wooden spoon, or an old bullwhip, or with her bare hands. And while I feared these beatings I didn’t think them odd or bad; I knew no other kind of affection, and neither did Nena. She used her fists to teach me things she couldn’t articulate, lessons that would keep me alive. Nena could keep me safe in her kitchen but nowhere else. I was a creature without family or money. I was another mouth to feed. And, even worse, I was a girl. At the owners’ whim, I could be thrown out of the Great House and left to fend for myself in that sea of sugarcane. And what did an ugly little girl have to offer the world but he...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherRiverhead Books

- Publication date2019

- ISBN 10 0735211000

- ISBN 13 9780735211001

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages528

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.25

From Canada to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Air You Breathe

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Paperback. Publisher overstock, may contain remainder mark on edge. Seller Inventory # 9780735211001B

Air You Breathe

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 35556376-n

The Air You Breathe: A Novel

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New! Not Overstocks or Low Quality Book Club Editions! Direct From the Publisher! We're not a giant, faceless warehouse organization! We're a small town bookstore that loves books and loves it's customers! Buy from Lakeside Books!. Seller Inventory # OTF-S-9780735211001

The Air You Breathe: A Novel by de Pontes Peebles, Frances [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9780735211001

The Air You Breathe: A Novel

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0735211000-2-1

The Air You Breathe: A Novel

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0735211000-new

TheAirYouBreathe Format: Paperback

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 0735211000

The Air You Breathe (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. The Air You Breathe 0.8. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9780735211001

The Air You Breathe: A Novel

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # 0735211000

The Air You Breathe: A Novel

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # I-9780735211001