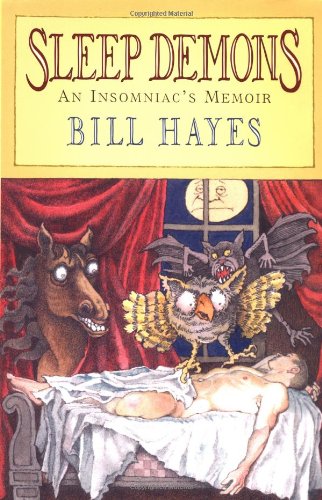

Items related to Sleep Demons: An Insomniac's Memoir

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Chapter 1: In Utero

I grew up in a family where the question "How'd you sleep?" was a topic of genuine reflection at the breakfast table. My five sisters and I each rated the last night's particular qualities -- when we fell asleep, how often we woke, what we dreamed, if we dreamed. My father's response influenced the family's mood for the day: if "lousy," the rest of us felt lousy, too. If there's such a thing as an insomnia gene, Dad passed it on to me, along with his green eyes and Irish melancholy.

I lay awake as a young boy, my mind racing like the spell-check function on a computer, scanning all data, lighting on images, moments, fragments of conversation, impossible to turn off. As a sleeping aid, I would try to recall my entire life -- a straight narrative from first to last incident -- thereby imposing order on the inventory of desire and memory. My story always started with a plane ride from Minneapolis to Spokane -- a trip that actually occurred, the recollection of which, however, may be imaginary. I was no older than three. But there I am regardless, in memory as if in a movie, still gazing out the window of a jet.

If my boyhood story didn't lull me to sleep, I'd sneak into the den, where I could find my mother, watching Johnny Carson and drinking Coca-Cola, simultaneously smoking Pall Malls and folding laundry. For her, I suspect, not sleeping offered time on her own. For me, visiting Mom after midnight was the only time I had her to myself in such a big family. She never shooed me back to bed. I helped her fold socks, she gave me a glass of Coke. Some combination of the two helped me fall asleep.

After she had put me to bed, I would occasionally wander back again, sleepwalking. I remembered nothing of these night visits. I learned of them at the breakfast table, next morning, where they were a source of laughter from my sisters that left me uneasy. Thirty years later, my mother still recalls how oddly I acted: I did not sit down with her, didn't speak or respond to her voice. I appeared to be looking for something. Without waking me, she would gently lead me back to my room. This sleep disorder, a "parasomnia" that rarely appears in adults, lasted about two years.

In some ways, I find sleepwalking more perplexing than sleeplessness -- perhaps because it afflicted me while I was so young, then let me go, never to return again. If the insomniac is a shadow of his daylight self, existing nightlong on nothing but the fumes of consciousness, then the somnambulist is like an animal whose back leg drags a steel trap -- the mind is fleeing and the body is inextricably attached.

Where did I want to go? Out of that house, I imagine. Away from the person I saw myself becoming. Toward a dreamed-up boy, with a new story, a different version of myself.

Now, halfway through my life, I still wander at night. I still seek the peerless soporific. Everybody has a cure to recommend, whether it's warm milk, frisky sex, or melatonin. One friend solemnly prescribes whiffing dirty socks before turning out the lights. I find, though, that home remedies are no more effective than aphrodisiacs. Sleeping pills can force the body into unconsciousness, it's true. I've had my jags on Halcion and Xanax, Ambien and Restoril. I've slept many times on those delicious, light-blue pillows. But the body is never really tricked. The difference between drugged and natural sleep eventually reveals itself, like the difference between an affair and true romance. It shows up in your eyes. Sleep acts, in this regard, more like an emotion than a bodily function. As with desire, it resists pursuit. Sleep must come find you.

Nevertheless, I look for it. If not my own, then the sleep of others. You might find me on the subway staring as you come out of a snooze. You'd see no guilt on my face for watching so shamelessly, only fascination. When people doze in public, the human animal comes out. They burrow into their own clothing or nestle into a friend's shoulder. Undefended from their own small indiscretions, they scratch, grunt, fart, drool, grit their teeth. People know this happens and try to hide themselves: they pull down a hat or put on sunglasses; duck under a newspaper or drape an arm over the face. Left exposed, it is as if they're caught naked: a hand instinctively reaches up to shield their eyes, where it often remains until the lids open.

Sleep also has the uncanny ability both to infantilize and to age, which is especially strange to see in the person with whom you are intimate. After a night of insomnia, sometimes I stand at the bedroom door, coffee in hand, watching my partner of ten years, Steve, sleep. One morning, he's curled up in the fetal position, legs tucked up to his chest, arms hugging a pillow. He looks as vulnerable as a baby. With a snort, he rolls onto his back, the planes of his face fall into shadows, and suddenly he's middle-aged. Another morning, Steve sleeps so soundlessly I have to make sure he's still breathing. I tiptoe in and hover over him. I hold my own breath, not making a sound. Yet it is as if his sleeping self recognizes me -- it vanishes in a heartbeat. He wakes up, startled, wondering what the hell I'm doing.

Sleep scientists spend their entire waking lives engaged in this kind of surveillance. They may stay up all night just to watch someone awaken. They treat bizarre and dangerous disorders -- narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, African sleeping sickness, fatal familial insomnia -- as well as the everyday sleep disturbances of people like me. I've looked into their findings, in search of answers that my own body refuses to divulge. I've studied the work of early sleep researchers, along with books on anatomy, mythology, mental disorders, aging. While none of what I've learned has fully unraveled the mystery of sleep, least of all in my own life, I have come to see that sleep itself tells a story.

The ancient Greeks envisioned sleep to be Hypnos, the twin brother of death, Thanatos. A minor god, born of Night, Hypnos lived in a dark, underworld cave on the island of Lemnos. The River of Forgetfulness flowed through the cavern where Hypnos lay on pillows surrounded by his many sons, including Morpheus, the dream-bringer. Unlike his twin, Hypnos was considered a friend of mortals, a healer of body and mind. He took different forms as he wandered the earth -- a bird or a child, but most often a benevolent warrior carrying a horn, from which he would drip a sleep elixir. The Greeks apparently took his gifts for granted. There were neither temples devoted to Hypnos nor songs to thank him. No cult arose to worship sleep, which seems particularly odd, if not irreverent, for surely there were ancient insomniacs.

A Greek physician named Alcmaeon, from the sixth century B.C., is credited with the first recorded theory on the cause of sleep. He thought it was due to blood vessels of the brain becoming engorged. Aristotle, two hundred years later, viewed sleep as the opposite of wakefulness, one of the contraries that "are seen always to present themselves in the same subject, and to be affections of the same: examples are -- health and sickness, beauty and ugliness, strength and weakness, sight and blindness, hearing and deafness." In a sense, Aristotle took the Greek myth and recast it: now, sleep was the evil twin of wakefulness. "Sleep," he noted, "is evidently a privation of waking." Basing his theory on personal observation rather than traditional thought, Aristotle concluded that sleep was the result of vapors generated by the digestion of food, which then rose to the brain. The bigger the meal, the greater the vapors, the sleepier one got.

Aristotle's ideas remained influential for centuries. Experts who followed devoted themselves to hunting down sleep to its anatomical root, if only in hope of extending wakefulness. If not in the stomach, then possibly behind the eyes? The thyroid, at the base of the neck, was thought to be a sleep-inducing gland until doctors recognized that removing it did not cause insomnia. Another example -- nonsensical in hindsight -- can be found in David Hartley's Observations on Man: His Frame, His Duty, and His Expectations, published more than two thousand years after Aristotle, in 1749. Inquiring into "the intimate and precise nature of sleep," Hartley, an English doctor, stated that sleep could be explained by the "Doctrine of Vibrations." As he saw it, the human body was like a sack of Jell-O -- a jiggling mass of solids and fluids. It must, on occasion, come to rest. To Hartley and his contemporaries, sleep was considered necessary but intrinsically bad. Oversleeping (or, heaven forbid, enjoying sleep) demonstrated a character flaw; it was a symptom of sloth and low intelligence.

By the early twentieth century, proposed theories weren't any more accurate. According to the French scientist Claparède, sleep resulted from a loss of interest in one's surroundings (réaction de désintér234;t); likewise, one woke up because one tired of sleeping. This "instinct" was thought to serve an essential defensive function: "We sleep not because we are intoxicated or exhausted," Claparède wrote in 1905, "but in order to prevent our becoming intoxicated or exhausted." It was like saying that we breathe in order not to die of asphyxiation, as later scientists pointed out. His theory was related to a prevailing idea that sleep was caused by mysterious toxins in the blood, the "products of wakefulness." Long popular, this "hypnotoxin theory" held that fatigue was a poisonous substance that built up over the day, finally causing sleep at night, at which time it was eliminated. The more you slept, the more you had been bedeviled by the day's toxins.

The notion that we are poisoned and possessed by sleep would've made perfect sense to me as a little boy. That's how my parents and sisters appeared when I looked in on them. Awakened by a stomachache or bad dream, I would sometimes scurry down the chilly hall to Mom and Dad's room, two doors away, right after the kids' bathroom. (In our home, where every room conveyed its rank in the family hierarchy, each with its own set of rules, the title "the master bedroom" was especially apt.) Having pushed open their door, I'd pause in the entryway, just past the master bathroom, and peer around the corner toward where they slept.

They had twin beds, pushed together, united by a teakwood headboard and a single quilt. Watching their lumpish figures, like the dark mounds of snow piled at either side of our driveway, I felt scared for a moment. They were there, but not present: faces buried in pillows; breathing raspily; tongues clacking. I stepped forward. Then it was I who scared them. Mom would wake with a sudden gasp -- feet on the floor even before she recognized which child stood before her. She'd whisk me back to my room as Dad's figure half-rose in the background. His sleep, we all understood, was not to be disturbed.

I never crawled into bed with them. None of us kids did. But when I was a bit older, ten or eleven, I had to share a bed with my father on occasional weekend ski trips -- promoted in advance as "just for the boys." As Dad merrily explained to my sisters, "No squaws allowed."

I was used to sleeping by myself. I can still recall my dread as we got into bed at the ski lodge. Lying on my back, feeling pinioned between the starched sheets, I could hear a transformation take place after Dad said good-night and turned out the lights. Maybe he took a Valium, as he sometimes did at home. His breathing, at first silent, steadily became pronounced. If I turned to face him, I'd be bathed in it, a warm blast of toothpaste and Johnnie Walker. I rolled in the other direction. The room was overheated, the pillow too hard. It's simple, I coached myself: relax, breathe with him, and you'll fall asleep. So I modulated my breathing to be syncopated with his. But it was no use. In minutes, I'd lose track or fail to keep his rhythm. I'd lie awake, wedged between my father and the wall.

What really happens to a person who goes without sleep? A young doctoral student, Nathaniel Kleitman, kept himself awake for five days in the early 1920s to try to answer this question. His experiment, repeated dozens of times and involving several other subjects, was one of the first systematic studies of sleep deprivation; it became the basis of his physiology dissertation at the University of Chicago. Kleitman's research led to two intriguing conclusions. First, people who stayed up all night were actually more alert in the morning than they'd been in the middle of the sleepless night. Second, after about sixty hours of being awake, the ill effects of sleeplessness appeared to level off; health and behavior did not further degenerate even if sleep deprivation continued. Both findings invalidated the theory that fatigue-inducing toxins progressively accumulated in the body.

The hypnotoxin myth was one of many debunked by Dr. Kleitman. In an extraordinary fifty-year career, he revolutionized and modernized the study of sleep. He established the country's first sleep research laboratory, where he conducted rigorous experiments on animal and human subjects, often including himself; wrote a definitive scientific text, Sleep and Wakefulness, first published in 1939, which remains in print today; and in collaboration with others, made seminal discoveries about the stages of normal sleep, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and dreaming. Kleitman is often called, reverentially, the Dean of Sleep Research, yet the image I have of him evokes a very different title.

In an enlarged Xerox copy of a grainy 1938 newspaper photograph that hangs above my desk, he is emerging from Mammoth Cave, Kentucky, in which he and an assistant had spent thirty-two consecutive days carrying out a primitive experiment. A tall, bearded man in a black robe, Kleitman materializes from darkness, followed by a second bearded man, B. H. Richardson, in the same flowing attire. Kleitman's face is bleached as white as the druidic hood covering his head. Stunned by flashbulbs, he looks as if he's been captured against his will. He holds a kerosene lamp in his left hand. Other details are lost to the inky blackness, yet a wild look remains in his beady eyes -- the look of a man who has been to the underworld and back. It is Hypnos himself, together with Morpheus.

They lived in near total isolation from the outside world, seeking nothing less than to challenge the "cosmic forces," as Kleitman put it, that mandate the twenty-four-hour ("circadian") cycle of sleep and wakefulness. In their experiment, Kleitman and Richardson attempted to adjust to a twenty-eight-hour schedule -- nineteen wakeful hours and nine in bed -- a six-day week. Although food was left for them daily, and a photographer apparently visited once, "subjects R and K," as Kleitman identified his assistant and himself in scientific literature, had virtually no contact with others.

"The darkness was absolute...; the silence was also complete; and the temperature was always 54 degrees Fahrenheit," Kleitman wrote of their deep cavern home, which measured sixty feet wide and twenty-five feet high. The only unpleasan...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherWashington Square Press

- Publication date2001

- ISBN 10 0671028146

- ISBN 13 9780671028145

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages368

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Sleep Demons: An Insomniac's Memoir

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0671028146

Sleep Demons: An Insomniac's Memoir

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0671028146

Sleep Demons: An Insomniac's Memoir

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0671028146

Sleep Demons: An Insomniac's Memoir

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0671028146

Sleep Demons: An Insomniac's Memoir

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0671028146

Sleep Demons: An Insomniac's Memoir

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB0671028146

SLEEP DEMONS: AN INSOMNIAC'S MEM

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.7. Seller Inventory # Q-0671028146