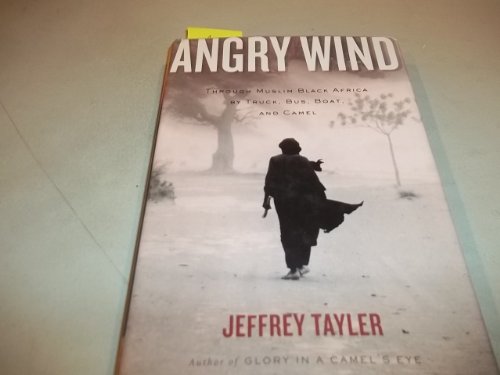

Items related to Angry Wind: Through Muslim Black Africa by Truck, Bus,...

Traveling overland by the same rickety means used by the local people--tottering, overfilled buses, bush taxis with holes in the floor, disgruntled camels--he uses his fluency in French and Arabic (the region’s lingua francas) to connect with them. Tayler is able to illuminate the roiling, enigmatic cultures of the Sahel as no other Western writer could.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

It was July 1997. Panting and dizzy from the heat, I clambered atop the torrid sandstone brow of Dala Hill and squinted through the noontime glare at the Nigerian city of Kano below. From the hill’s base spread a rough-hewn maze of zigzagging sandy lanes and squat mud hovels. Farther away, to the south, stood the emerald green minaret of a great walled mosque; beyond that, from the roofs of distant earthen houses, rose stabbing, man-size crenellations that, though molded from clay, resembled nothing other than giant sharks’ teeth, curved and deadly.

Sarki, my Hausa guide, spread his arms and gestured beyond the houses at the land beyond: flat, tawny barrens, dotted with thorny scrub and gnarled trees, sweeping away into a blazing whiteout haze terrain as sere and harsh as the desert but without the desert’s charm.

The Sahel!” Sarki declared. East is Chad, north is Niger, and to the west is Mali.” Chad, Niger, Mali . . . lands of famine and drought, Islam and guerilla warfare; in short, sun-bleached, barbarous realms where, for centuries, exotic kingdoms had flourished and eventually fallen to the sabers of invading Arabs and the guns of colonizing Europeans. As I stood on Dala Hill that day, that was about all I knew, or thought I knew, of those countries, but their names, conjuring up alien peoples and vague perils, stirred and intrigued me. They even seemed to present me with some sort of challenge.

Sarki’s name in Hausa meant king,” and he had the look of royalty about him. In his early forties, wearing long white robes and a crested white turban, with the tight skin on his gaunt cheeks and aquiline nose glistening like oiled mahogany, he possessed the imperious mien of an Islamic suzerain. As I looked at him, a flood of unfamiliar words came to mind: khedive, dey, nabob, emir legend-laden titles of Arab and Turkish potentates of whose likes I had only read. Sarki was a Muslim, but he was black, a speaker of an African language peppered with Arabic loan words, a member of the Hausa a people about whom I knew little, except that they had resisted Western influence during Nigeria’s colonial days and afterward, and were among the most fervent Islamic fundamentalists pushing for the imposition of shari’a, or Islamic law, in the northern states of the country.

With sweat dripping into my eyes, I followed Sarki off the hill and into the maze of old Kano. The assault on my heat-addled senses was immediate and relentless. Shrouded lepers with leaking sores and yellowed eyes swarmed around me, sticking their stumps in my face and whining for alms. Hordes of barefoot children in smocks came running to tug at my shirt and shout Masta! Masta!” and rattle their tins. I winced at the sight of a man in rags ambling by, jaw agog, his teeth sprouting horizontally through his cheeks. From the dark innards of alley-side workshops came the ear- shattering pounding of hammers and the screechy creaking of looms; from the open doors of Islamic schools resounded Qur’anic chants as deafening as they were monotonous. Pushing my way through the crowd, clinging close to Sarki and unable to understand a word he shouted to me, I inhaled air heavy with sweat and the cloying reek of wet clay and open sewers; often I stumbled, my eyes failing to adjust to the flaming pools of white sun alternating with columns of black shade cast by the beams stretching over the alleys. I wanted nothing more than to escape.

Once we were out of the alleys and past the beggars, Sarki, strolling at ease, expounded in his bass, pidgin-inflected English on the history of Kano, or, rather, on the legend of Kano’s birth. The people of Kano, like the rest of the Hausa in Nigeria’s mostly Muslim north, were not really Africans, he contended, but traced their lineage to a renegade Arab prince from Baghdad, Bayajida, who came here, killed a fearsome snake, married the queen, and fathered the children who would establish seven Hausa city- states, of which Kano would become the most prominent. This legend granted the Hausa a bloodline leading back to the progenitors of Islam, a religion the Hausa began accepting only in the fifteenth century after their king converted. What is certain is that the king’s conversion brought close ties with Arabia and the North African Arabs who ran the trans-Saharan trade on which Kano and the other Hausa states would flourish. It also brought the Arabic language, in which the Hausa chronicled their cities’ history and whose alphabet they later adopted to write their own tongue.

Talking to Sarki, I would never have guessed that Islamic Kano belonged to the same country as did the city from which I had just arrived, Lagos a festive but violent, mostly Christian, and definitely African shantytown of 13 million people built on the malarial swamps and jungleeeee lagoons of the Gulf of Guinea, seven hundred miles to the southwest. Within the walls of old Kano alcohol was forbidden and crime was rare. Kano’s Hausa inhabitants, aloof and dressed in robes of green, white, and blue, exchanged formulaic Arabic greetings and mingled with indigo-robed Nigériens and visiting Libyan traders. A mercantile spirit ruled: Christian workers (Yoruba and Igbo from the south) loaded donkey carts for hectoring Muslim bosses, and every corner bustled with commerce. Only when Kano’s emir, or traditional Islamic ruler, appeared on horseback to deliver his Friday sermon at the central mosque would the din stop.

The emir’s word is our law,” said Sarki. The federal government must get his approval before it acts in Kano.” We wandered through the dust-choked lanes in search of lion oil” to cure the backache of one of Sarki’s friends. Sarki introduced me to all sorts of Hausa traders and relatives. They expressed disdain for Christian southerners and blamed them for Nigeria’s most notorious problems armed robbery, drug trafficking, and fraud.

Because of Islam, sons of Hausa would be afraid and ashamed to steal. Armed robbers come from the south,” Sarki said. All agreed.

We stopped by a poster of Mu’ammar al-Gadda., bearing the Arabic inscription AL-AKH QA’ID AL-THAWRA [Our Brother and the Leader of the Revolution] MU’AMMAR AL-GADDAFI. Sarki looked up at the turbaned Libyan. We feel solidarity with Gadda., a true power-man who tells the truth. He calls for us Muslims to unite!” When Sarki spoke, it was easy to forget that he was a citizen of a country where those he dismissed as thieving southern Christians” make up 40 percent of a population of 130 million. Listening to him, one might also forget that his ethnic and religious group had done much, through malfeasance, corruption, and outright theft, to reduce to penury, civil strife, and decay what could be, thanks to huge oil and natural gas deposits, the wealthiest country in Africa. Four of Nigeria’s six military dictators (the last of whom died in 1998) have been Muslims from the north. Northern Nigeria needs southern Nigeria for its oil, its farmlands, and its ports, so Nigerian dictators have been bent on keeping united the fractious country, a designation that even a famous Nigerian nationalist called a mere geographical expression.” Conflicts between the Muslims of the north and the Christians of the south frequently erupt into deadly riots and outright insurrections that federal security forces quell with much loss of life.

On a crowded street just off Kofar Mata Road, the old town’s main thoroughfare, we finally found a shop selling lion oil.” The merchant used a knife to spear gobs of the honeylike substance and slip them into a plastic bag. What was it, exactly? I asked. Sarki couldn’t or wouldn’t say. (Perhaps it was some sort of secret folk medicine an infidel like me should know nothing about.) Smiling, he paid, and we stepped back out into the din and said goodbye.

Under a rattling air conditioner, I lay in my hotel bed that night and reflected on the disorienting, disturbing nature of what I had seen, smelled, heard, and felt during the day. I had been traveling and living abroad for half my life and had spent several years in North Africa and the Middle East, but everything in Kano seemed as new, frightening, and shocking as it was intriguing. The Muslim-Christian animosity; the African language studded with Arabic words; the crowds of desperate mendicants dwelling in medieval squalor in the middle of the second-largest city of what should have been Africa’s wealthiest country; and beyond the shark-tooth crenellations, the infinity of sun-baked wasteland stretching away into turbulent countries of which I knew so little all this left me with the prefatory burn of a new obsession for which I would be willing to risk my life, a challenge I would one day return to take up.

I did not make it back to sub-Saharan Africa before September 11, 2001, but the terrorist attacks of that day rekindled my fascination with the Sahel (still largely ignored by the Western media, despite all their newfound interest in the Islamic world) and prompted me to begin reading up on the region with renewed urgency. The Sahel, whose name comes from the Arabic sahil, or coast,” is an expanse of badlands, semidesert, and parched savanna that forms the southern shore of the Saharan sand sea and spreads some 3,000 miles across Africa from Ethiopia west to the Atlantic Ocean. My history books told me that in the countries of the Sahel specifically in Sudan, Chad, Nigeria, Niger, and Mali once thrived some of Africa’s wealthiest, if obscurest, kingdoms and empires, whose borders bore no relation to modern- day frontiers. The kingdoms of Wadai and Kanem, the Hausa emirates, the sultanate of Zinder and the Sokoto caliphate, and the Malian and Songhai empires prospered on the trans-Saharan trade in gold, salt, ivory, and slaves.

Arab chroniclers tell us what is known about the region’s precolonial history. In the seventh and eighth centuries, as Arab merchants began navigating ancient trade routes south across the Sahara, they encountered flourishing and orderly Sahelian kingdoms whose inhabitants regarded themselves as superior to outsiders. The Sahelians were practical, however, and to facilitate trade began adopting Islam, and with it the Arabic alphabet and much Arab culture. (The Arabs had a lot to teach in the Middle Ages: to them at that time belonged the most advanced literature, medicine, science, and law in the Eastern Hemisphere.) Hence, its predominantly Muslim faith makes Sahel” a cultural as well as a geographic designation. One might as well just call it Muslim black Africa.

Just as before September 11 Afghanistan drew few Western journalists, the Sahel, for decades beset by ethnic rebellion, sectarian violence, and banditry, receives little attention from the media today. Few areas of the world are as difficult to travel, to be sure, but there is another reason for the dearth of coverage: the countries of the Sahel don’t appear to affect the West. With the exception of oil-rich Nigeria, they play a negligible role in the global economy. Poverty in the Sahel is some of the worst on earth: between 45 percent (in Nigeria) and 80 percent (in Chad) live below the poverty line. Niger is the second-poorest country in the world, after Sierra Leone. Most Sahelians survive or don’t on half a dollar a day or less. Desertification (which stems from a combination of overgrazing and climate change and by some estimates is pushing the Sahara south at the rate of 3.5 miles a year) menaces what agriculture there is. The armies of the Sahel threaten no one beyond its borders, and no cold war now exists to spark great power rivalry over the region’s resources, which, besides uranium in Niger and oil in Nigeria, are minimal. AIDS is less of a problem in the Sahel than elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa: population- wide infection rates range from 1.4 percent in Senegal to 5 7 percent in Chad, high by Western standards, but not enough to make the news. When one hears of the Sahel at all, it is usually in connection with donor fatigue or drought. In short, for most Westerners, the Sahel is not on the map.

We can no longer afford such ignorance, for men dwelling in caves in a failed state as destitute as any in the Sahel orchestrated attacks that killed thousands of Americans on September 11. Al-Qa’ida has been active in Africa, perpetrating acts of terrorism in Kenya, Tanzania, and Tunisia that have cost the lives of hundreds of people. One Sahelian state, Sudan, sheltered Osama bin Laden until 1996. Al-Qa’ida and similar organizations are now believed to be operating in nine countries of sub-Saharan Africa, three of which are in the Sahel, where terrorist dollars go a long way in bribing officials for support, where government control of vast regions is minimal, where ill-trained police forces and ragtag armies can do little more than oppress their own people, and where local populations, Muslim and poor and increasingly anti-Western, may sympathize with Islamic radicals. Under the auspices of a program called the Pan-Sahel Initiative, the U.S. military is already helping Mali, Niger, and Chad pursue Islamic militants operating on their territories.

Any state in the Sahel could serve as a base for Al-Qa’ida, but Nigeria deserves special attention in this connection. The U.S. alliance with the Saudi regime rests largely on oil just as does America’s relationship with Nigeria, possessor of the tenth-largest reserves of crude in the world, and Washington’s new strategic energy partner. For years Nigeria has been the fifth-largest supplier of crude oil to the United States. By 2007, thanks to deals the Bush administration is concluding with Abuja, it will be the third.

Growing uncertainty over the future of the Saudi monarchy has prompted the United States to search for more stable sources of energy; hence its interest in Nigeria. But the U.S.-Nigeria relationship is fraught with perils similar to, or worse than, those bedeviling the Saudi alliance. For more than forty years Western multinationals have pumped oil from the Niger River Delta as the Nigerian government has battled villagers demanding their fair share of the wealth. Enter Osama bin Laden, who in February 2003 called Nigeria ripe for liberation” an ominous declaration, given the spread of Islamic extremism in the country. Ever since the death of the dictator General Sani Abacha in 1998 and the introduction of new freedoms, Islamic fundamentalism has threatened the secular principles of the Nigerian state, and even the unity of the country. Over the past four years, twelve northern Nigerian states have adopted shari’a law, to the rising fury of the country’s Christians. Since 1999 more than ten thousand Nigerians have died in vicious tribal and intercommunal clashes. The latest explosion came in November 2002 when women gathered in Abuja to compete in the Miss World pageant. A (Christian) Nigerian journalist contended in a national newspaper that the prophet Muhammad would have been pleased to choose a wife from among its contestants a remark that legions of Nigerian Muslims took as an anti- Islamic outrage and an insult that implied, they said, that the Prophet would have approved of Western debauchery. The four days of rioting that erupted between Muslims and Christians left 220 dead, 1,000 injured, and 11,000 homeless, and twenty churches and eight mosques burnt to the ground. Unfortunately, this mayhem stands out only because the Western press reported it; worse bouts of religiously inspired rioting in Nigeria have resulted in much higher death tolls.

Religious ire mixed with hatred for corrupt Arab rulers partly motivated the hijackers of September 11 to attack their regimes’ main ally, the United States. The people of oil-rich Nigeria are much, much poorer, and corruption is worse. In 2001 Trans...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHoughton Mifflin Harcourt

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 061833467X

- ISBN 13 9780618334674

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Angry Wind: Through Muslim Black Africa by Truck, Bus, Boat, and Camel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_061833467X

Angry Wind: Through Muslim Black Africa by Truck, Bus, Boat, and Camel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new061833467X

Angry Wind: Through Muslim Black Africa by Truck, Bus, Boat, and Camel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think061833467X

Angry Wind: Through Muslim Black Africa by Truck, Bus, Boat, and Camel

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover061833467X

ANGRY WIND: THROUGH MUSLIM BLACK

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.7. Seller Inventory # Q-061833467X