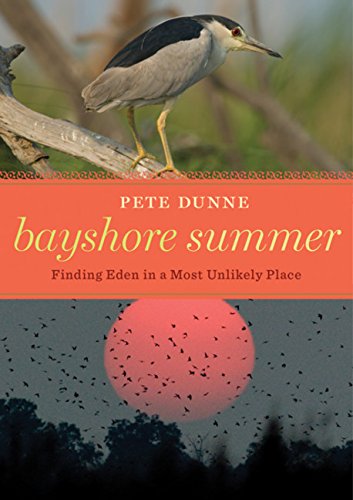

Items related to Bayshore Summer: Finding Eden in a Most Unlikely Place

Bayshore Summer is a bridge that links the rest of the world to this timeless land. Pete Dunne acts as ambassador and tour guide, following Bayshore residents as they haul crab traps, bale salt hay, stake out deer poachers, and pick tomatoes. He examines and appreciates this fertile land, how we live off it and how all of us connect with it. From the shorebirds that converge by the thousands to gorge themselves on crab eggs to the delicious fresh produce that earned the Garden State its nickname, from the line-dropping expectancy of party boat fishing to the waterman who lives on a first-name basis with the birds around his boat, Bayshore Summer is at once an expansive and intimate portrait of a special place, a secret Eden, and a glimpse into a world as rich as summer and enduring as a whispered promise.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Chapter 1

Sex and Gluttony on Delaware Bay

Before my hand found third gear, New Jersey's famed pine barrens had closed in on both sides of the road, buffering us from the Wawa and its mayhem. Much of eastern Cumberland County falls within the boundaries of the Pinelands National Reserve-a 1.1-million-acre tract of mostly forested land. Not a park or refuge where human endeavors are strictly proscribed, the reserve is a jurisdictional hybrid

according protection to areas of high environmental or cultural value and permitting compatible development in

others. Created by Congress in 1978, operating under a comprehensive management plan, and governed by the representatively diverse Pinelands Commission, both the reserve and the plan are variously acclaimed and decried.

People who want to see the environmental and cultural heritage of the region preserved generally applaud it. Large property owners and developers whose ambitions might undermine environmentally sensitive areas commonly fault it.

Like it or not, what is certain is that this creative initiative resulted in the protection of 22 percent of the most crowded state in the Union and preserved the largest body of open space between Boston and Richmond. Those shorebound travelers taking old Route 47, as Linda and I had done, are tracing the southern boundary of the preserve.

For some reason, the Delaware Bayshore was not placed beneath the umbrella of the reserve's protection. Its heritage and biological riches have, thus far, been preserved largely as a result of good fortune.

We passed several turnoffs, marked by weathered signs, directing travelers to communities with names that skirt all but local recognition-names such as Dorchester (pronounced, in the syllable-compressing dialect of the bayshore, DOR-ster), Leesburg, and Heislerville. While few travelers ever do turn off to explore these obscure towns, those who do wander into a New Jersey that is alien to nine out of ten residents of the state.

A land of black ducks and blue mud. Tight-knit communities composed of cedar-roofed and dowel-framed houses that hark back to a time when two-masted schooners and two-story homes were built by the same men.

Pickup trucks, not cars, occupy most of the driveways. Cats keep watch from behind age-rippled glass, and dogs, slumbering on porches, stir only at the sound of unfamiliar feet. And when you happen, as is certain you will, upon one of the old church cemeteries that command the high ground, you'll find the gate unlocked and age-blackened stones bearing the same names as the mailboxes you just passed.

Until recently, saying you lived on the bayshore was as good as saying you were born on the bayshore. This means you have roots that go back very far.

Not every road off Route 47 delivers as promised. Travelers bold enough to follow now rusting highway signs to Moores Beach and Thompsons Beach are headed for consternation. In two decades, these bayside communities went from shore towns to ghost towns to no towns as the roads leading out to them surrendered to marsh and the houses fell (literally) under the dominion of the tide.

Today, if you own a four-wheel-drive vehicle that you don't mind marinating in salt water, you can still drive to Moores Beach and the rubble-strewn strip of sand that borders the bay and once supported a town. But the road leading out to Thompsons Beach is impassable and gated. Beneath its blanket of salt grass there is macadam. At low tide it is navigable to foot traffic (or, more accurately, knee-high-boot traffic). But under the very best of conditions, the road that once led to this fishing community is treacherous. A person (or persons) would have to be very foolish, or very motivated, to attempt it.

Blue Mud

“Eahhh!” Linda cried, the sound of her protest barely audible over the cries of laughing gulls and the belly-laugh grunts of clapper rails-both of which are common summer residents.

“What?” I asked, turning, looking back at my wife, who was swaying, ominously, at a better than twenty-three-degree list, in the middle of a puddle that was the size and depth of a kiddie pool, though a good deal muddier.

Why ominously? Because the pack on her back was crammed with about twenty thousand dollars' worth of camera equipment and, as the Nikon owner's manual cautions, digital cameras and salt water don't mix.

Linda's no stranger to portaging stuff on her back. A onetime National Outdoor Leadership School instructor, she once climbed Denali wearing a hundred-pound pack-a pack that weighed as much as she did. Concluding, therefore, that ballast was not the source of my wife's consternation, I explored the possibility of an equipment malfunction.

“Boots leak?” I asked, when her gyrations had stabilized enough to support conversation.

“No!” she shouted. “They're too large. The muck keeps sucking them off my fee--Ehh; ahhhh.”

I tensed as Linda survived another arm-swinging battle with gravity. Search the world over, you'll find hardly anything more slick, slimy, and boot-suckingly treacherous than good ol' Delaware Bay blue mud. The fine particulate matter, ferried and deposited by the waters of the Delaware River, has the color and consistency of graphite and the sulfurous smell of hell. Dark spatterings of the stuff were already marring Linda's pretty face. But since she wasn't going to be on the receiving side of the cameras she was carrying, it hardly mattered.

“We're almost there,” I encouraged. “The road's better ahead.” This was true as far as it went. What I didn't say, which was also true, was “and then it gets worse again.”

Ten minutes later, our boots, still numbering four, were planted on packed white sand. In front of us was a sun-splashed Delaware Bay. Around us the rubble that used to be Thompsons Beach.

“There are no birds,” Linda couldn't help noticing.

“Well, there were,” I asserted.

“When?” she wanted to know.

“About twenty years ago,” I said, smiling quickly to let her know it was a joke.

“This way,” I said, turning east. “Another quarter mile. I scouted it yesterday. An hour earlier. The tide should be about the same, and there absolutely were birds.”

“Including knots?” she asked, pinning a name to the poster bird of Delaware Bay's famed spring shorebird concentrations.

“Including knots,” I said. “Some. Ready to go?”

She was, and we did. Walked east along the narrow strip of sand and through the remains of the town. But I couldn't help thinking of the way it had been twenty years ago - both with the town and with the birds. And how the diminishment of what was one of the planet's greatest natural spectacles was anything but a joke.

Crabs and Shorebirds for Lunch

My introduction to the now-famous spectacle of spawning crabs and migrating shorebirds came in May 1977. I was responding to an invitation by Jim and Joan Seibert, residents of the bayside hamlet of Del Haven-a cluster of houses clinging to the land about halfway up the Cape May peninsula.

They said that the beach in front of their house was awash in birds.

“Fantastic,” they assessed. “Unbelievable,” they promised. “Come to lunch.”

I did. And while, as the newly minted naturalist for the incipient Cape May Bird Observatory, I would have come just to see the birds, the promise of a free lunch was irresistible.

Naturalists the world over are opportunistic feeders. Since my position with the New Jersey Audubon Society was earning me a whopping $250 a month, such flexible feeding habits had clear survival advantages. In this regard, naturalists are much like the shorebirds that concentrate here in spring. They, too, are in it for the eats.

Lunch was enjoyable, the birds as advertised. Fantastic, unbelievable. A pulsing, vibrating ribbon of shorebirds stretching as far as the eye could see - tiny gray-backed semipalmated sandpipers, sanderlings in their rarely seen brick red breeding plumage, harlequin-patterned ruddy turnstones, and, best of all, red knots! Big, burly, silver-backed shorebirds and high-Arctic breeders. There were more knots on that single stretch of beach than I'd ever dreamed of. More knots, as it turned out, than were estimated to be in all of North America.

But just as impressive, perhaps more, was the concentration of breeding horseshoe crabs, whose tiny gray-green eggs were the foundation and objective of the feeding birds-the tiny loaves that fed the multitudes.

Hubcap-sized, bronze-colored, and helmet-shaped, the 340-million-year-old sea creatures absolutely carpeted the beach. There were hundreds of larger female crabs, half buried in sand, and thousands of attending males.

To the crabs, it was all about sex. To the birds, it was all about gluttony.

Many years later, I would read an account of the spawning crabs written by Alexander Wilson, the father of American ornithology. Writing in the early 1800s of the stretch of beach east of the mouth of the Maurice River-the stretch of beach Linda and I were walking now-Wilson noted that a person could walk ten miles upon the carapaces of horseshoe crabs and never touch the sand.

It was this way, too, in 1977 and for about a decade after, and my experience here is firsthand.

Starting in 1981, I was part of a three-person team fly_ing aerial surveys to gauge the magnitude of the shorebird concentrations along New Jersey's bayshore. We counted a peak one-day total of 350,000 birds during those inaugural survey flights, including 67,000 red knots. The following year, adding the cross-bay beaches of the state of Delaware to the survey route, our totals reached 420,000 birds, including 95,000 red knots.

Given a turnover of fourteen days, biologists projected that a total of a million to perhaps a million and a half shorebirds were foraging on bayshore beaches between May 10 and June 10, making the spectacle on Delaware Bay one of the greatest concentrations of shorebirds on the planet. From there, fully fueled on the fat of reconstituted crab eggs, the birds would fly nonstop to Arctic breeding grounds and arrive in fine shape to go about the serious business of replicating the species.

The crabs were estimated to number 10 to 20 million, by far the greatest aggregation of this living fossil known to science. On every high tide, when the crabs would emerge, the shells in the surf sounded like crockery rattling in some great sink. As the tide receded, it looked as though the beaches were paved in animate cobblestones.

That was the celebrated phenomenon. An annual massed gathering of living things on the narrow beaches of Delaware Bay. Nobody knows how long it had been going on. But everybody knows how long it lasted after it was rediscovered. About fifteen years.

Knot Now

Past the pilings that once supported the homes and docks of Thompsons Beach, and the rubble that is all that is left of them, there is a quarter mile of open beach. The tide was still rising. Here and there along the old high-tide line were shallow craters that marked the location of newly deposited horseshoe crab eggs. Every ten yards or so, Linda and I encountered an overturned crab-mostly male. We righted these with our boots, to the annoyance of the onlooking host of herring gulls, who enjoy scavenging rights to all dead and dying crabs.

The winds, light and northerly, were projected to go slack, then southerly by afternoon. Good news for crabs and birds primed to migrate. Not so good for writers and photographers, who would have to contend with the clouds of biting midges called “no-see-ums.”

“Almost there,” I said once again to Linda, who was overturning crabs, so lagging behind. Near the mouth of the creek, projecting out into the bay, was a sod bank that the birds had been using at low tide. Birds were still there: a couple of dozen turnstones, and a handful of knots. It wasn't the throngs of birds we'd been hoping for, but at least the trip wouldn't be a total bust.

I reached the end of the beach. Edged myself around a tall stand of reed grass, and . . .

There, clustered about the sandy bar, were about a thousand shorebirds, all busily foraging for eggs. Lots of semipalmated sandpipers, lots of sanderlings, lots of ruddy turnstones, and best of all, lots of red knots-not the 6,000 that were reported to be up in the bay (about one third of the current estimated populations). But six hundred at least-most of them decked out in their breeding plumage, the silver backs and ruddy breasts that were the source of the old market gunners' name for the bird, “robin snipe.”

Linda turned the corner. Stared. Smiled. Here, on a spit of sand some forty feet wide and two hundred feet long, was a concentration of birds that harked back to the wonder and bounty that greeted visitors when shorebird numbers were at their peak.

Linda slipped out of her pack. Cracked the cover. Starting fitting lenses to cameras.

“I'll open the tripod,” I offered.

“Thanks,” she said.

“Are you going to stand or kneel?” I asked.

“Kneel,” she said. “Crawl. I want to be eye level with these birds. I want to taste horseshoe crab eggs. Do you want to shoot?”

“You might have to dig,” I said, suddenly conscious of the fact that the birds were not foraging on exposed eggs. All of them seemed to be probing and rooting. It was an adaptation I'd never seen. Back in the days of plenty, only the turnstones were egg mass excavators. Now, it seemed, all the successful birds were doing it.

“I'll leave you the two-hundred-to-four-hundred lens,” Linda said, not waiting for my reply. “It's set for program, and you've got a new memory card.”

“This is so awesome,” she said, lifting her camera fitted with her favorite 500-millimeter lens (named “Big Bertha”). “This is so cool,” she assessed. Then she waded slowly into the birds, whose ranks parted to receive her. In less than five minutes, Linda was seated in the sand and surrounded by birds. A 50-millimeter lens would have served her better.

It was awesome. It was affirming. In fact, it was perfect.

Almost perfect.

Undoing the Knot

I didn't start shooting immediately. And I didn't take notes, which, being the scribe in this endeavor, I should have been doing. What I did instead was savor. The spectacle. The day. The miracle that is a shorebird. The study in pure, applied hard-shelled tenacity that is a horseshoe crab.

The red knot, owing to the rapid and dramatic decline in its numbers, has been studied and written about extensively. In less than two decades' time, the population of the rufa subspecies, the subspecies whose strategy for survival seems tied to Delaware Bay, went from an estimated high of 160,000 to about 18,000. In cold, clinical mathematics, its population is now just over a tenth of what it was when I first set eyes on the spectacle, over thirty years ago.

The undoing of the phenomenon was unnecessary and preventable. But, as so often happens when our species ascribes value to another species, it happened anyway.

What happened? The overexploitation of a natural resource-one of the oldes...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherMariner Books

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 054719563X

- ISBN 13 9780547195636

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Bayshore Summer: Finding Eden in a Most Unlikely Place

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 5AUZZZ0005PK_ns

Bayshore Summer: Finding Eden in a Most Unlikely Place

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 52GZZZ00A174_ns

Bayshore Summer: Finding Eden in a Most Unlikely Place

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.75. Seller Inventory # 353-054719563X-new

Bayshore Summer: Finding Eden in a Most Unlikely Place

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 0.75. Seller Inventory # 054719563X-2-1

Bayshore Summer: Finding Eden in a Most Unlikely Place

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_054719563X

Bayshore Summer: Finding Eden in a Most Unlikely Place

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think054719563X

Bayshore Summer: Finding Eden in a Most Unlikely Place

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover054719563X

Bayshore Summer: Finding Eden in a Most Unlikely Place

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard054719563X

Bayshore Summer: Finding Eden in a Most Unlikely Place

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new054719563X

Bayshore Summer: Finding Eden in a Most Unlikely Place

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon054719563X