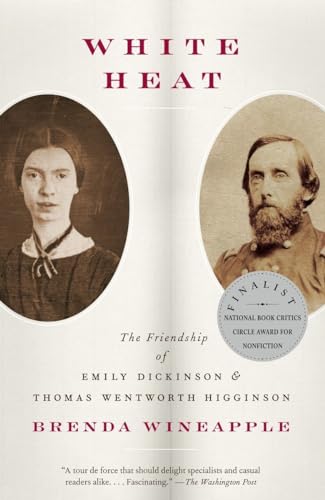

About the Author:

Brenda Wineapple is the author of Genet: A Biography of Janet Flanner; Sister Brother: Gertrude and Leo Stein; and Hawthorne: A Life, winner of the Ambassador Award of the English-Speaking Union for Best Biography of 2003. Her essays and reviews appear in many publications, among them The New York Times Book Review and The Nation. She has been the recipient of grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation. She lives in New York City and teaches creative writing at Columbia University and The New School.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

The LetterThis is my letter to the WorldThat never wrote to Me--The simple News that Nature told--With tender MajestyHer Message is committedTo Hands I cannot see--For love of Her--Sweet--countrymen--Judge tenderly--of MeReprinted by Thomas Wentworth Higginson and MabelLoomis Todd in Emily Dickinson, Poems (1890)Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?" Thomas Wentworth Higginson opened the cream-colored envelope as he walked home from the post office, where he had stopped on the mild spring morning of April 17 after watching young women lift dumbbells at the local gymnasium. The year was 1862, a war was raging, and Higginson, at thirty-eight, was the local authority on physical fitness. This was one of his causes, as were women's health and education. His passion, though, was for abolition. But dubious about President Lincoln's intentions--fighting to save the Union was not the same as fighting to abolish slavery-- he had not yet put on a blue uniform. Perhaps he should.Yet he was also a literary man (great consolation for inaction) and frequently published in the cultural magazine of the moment, The Atlantic Monthly, where, along with gymnastics, women's rights, and slavery, his subjects were flowers and birds and the changing seasons.Out fell a letter, scrawled in a looping, difficult hand, as well as four poems and another, smaller envelope. With difficulty he deciphered the scribble. "Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?"This is the beginning of a most extraordinary correspondence, which lasts almost a quarter of a century, until Emily Dickinson's death in 1886, and during which time the poet sent Higginson almost one hundred poems, many of her best, their metrical forms jagged, their punctuation unpredictable, their images honed to a fine point, their meaning elliptical, heart-gripping, electric. The poems hit their mark. Poetry torn up by the roots, he later said, that took his breath away.Today it may seem strange she would entrust them to the man now conventionally regarded as a hidebound reformer with a tin ear. But Dickinson had not picked Higginson at random. Suspecting he would be receptive, she also recognized a sensibility she could trust--that of a brave iconoclast conversant with botany, butterflies, and books and willing to risk everything for what he believed.At first she knew him only by reputation. His name, opinions, and sheer moxie were the stuff of headlines for years, for as a voluble man of causes, he was on record as loathing capital punishment, child labor, and the unfair laws depriving women of civil rights. An ordained minister, he had officiated at Lucy Stone's wedding, and after reading from a statement prepared by the bride and groom, he distributed it to fellow clergymen as a manual of marital parity.Above all, he detested slavery. One of the most steadfast and famous abolitionists in New England, he was far more radical than William Lloyd Garrison, if, that is, radicalism is measured by a willingness to entertain violence for the social good. Inequality offended him personally; so did passive resistance. Braced by the righteousness of his cause--the unequivocal emancipation of the slaves--this Massachusetts gentleman of the white and learned class had earned a reputation among his own as a lunatic. In 1854 he had battered down a courthouse door in Boston in an attempt to free the fugitive slave Anthony Burns. In 1856 he helped arm antislavery settlers in Kansas and, a loaded pistol in his belt, admitted almost sheepishly,"I enjoy danger." Afterward he preached sedition while furnishing money and morale to John Brown.All this had occurred by the time Dickinson asked him if he was too busy to read her poems, as if it were the most reasonable request in the world."The Mind is so near itself--it cannot see, distinctly--and I have none to ask--" she politely lied. Her brother, Austin, and his wife, Susan, lived right next door, and with Sue she regularly shared much of her verse. "Could I make you and Austin--proud--sometime--a great way off--'twould give me taller feet--," she confided. Yet Dickinson now sought an adviser unconnected to family. "Should you think it breathed--and had you the leisure to tell me," she told Higginson, "I should feel quick gratitude--."Should you think my poetry breathed; quick gratitude: if only he could write like this.Dickinson had opened her request bluntly. "Mr. Higginson," she scribbled at the top of the page. There was no other salutation. Nor did she provide a closing. Almost thirty years later Higginson still recalled that "the most curious thing about the letter was the total absence of a signature." And he well remembered that smaller sealed envelope, in which she had penciled her name on a card. "I enclose my name--asking you, if you please--Sir--to tell me what is true?" That envelope, discrete and alluring, was a strategy, a plea, a gambit.Higginson glanced over one of the four poems. "I'll tell you how the Sun rose-- / A Ribbon at a time--." Who writes like this? And another: "The nearest Dream recedes--unrealize--." The thrill of discovery still warm three decades later, he recollected that "the impression of a wholly new and original poetic genius was as distinct on my mind at the first reading of these four poems as it is now, after thirty years of further knowledge; and with it came the problem never yet solved, what place ought to be assigned in literature to what is so remarkable, yet so elusive of criticism." This was not the benign public verse of, say, John Greenleaf Whittier. It did not share the metrical perfection of a Longfellow or the tiresome "priapism" (Emerson's word, which Higginson liked to repeat) of Walt Whitman. It was unique, uncategorizable, itself.The Springfield Republican, a staple in the Dickinson family, regularly praised Higginson for his Atlantic essays. "I read your Chapters in the Atlantic--" Dickinson would tell him. Perhaps at Dickinson's behest, her sister-in-law had requested his daguerreotype from the Republican's editor, a family friend. As yet unbearded, his dark, thin hair falling to his ears, Higginson was nice looking; he dressed conventionally, and he had grit.Dickinson mailed her letter to Worcester, Massachusetts, where he lived and whose environs he had lovingly described: its lily ponds edged in emerald and the shadows of trees falling blue on a winter afternoon. She paid attention.He read another of the indelible poems she had enclosed.Safe in their Alabaster Chambers--Untouched by Morning--And untouched by noon--Sleep the meek members of the Resurrection,Rafter of Satin and Roof of Stone--Grand go the Years,In the Crescent above them--Worlds scoop their Arcs--And Firmaments--row--Diadems--drop--And Doges--surrender--Soundless as Dots,On a Disc of Snow.White alabaster chambers melt into snow, vanishing without sound: it's an unnerving image in a poem skeptical about the resurrection it proposes. The rhymes drift and tilt; its meter echoes that of Protestant hymns but derails. Dashes everywhere; caesuras where you least expect them, undeniable melodic control, polysyllabics eerily shifting to monosyllabics. Poor Higginson. Yet he knew he was holding something amazing, dropped from the sky, and he answered her in a way that pleased her.That he had received poems from an unknown woman did not entirely surprise him. He'd been getting a passel of mail ever since his article "Letter to a Young Contributor" had run earlier in the month. An advice column to readers who wanted to become Atlantic contributors, the essay offered some sensible tips for submitting work--use black ink, good pens, white paper--along with some patently didactic advice about writing. Work hard. Practice makes perfect. Press language to the uttermost. "There may be years of crowded passion in a word, and half a life in a sentence," he explained. "A single word may be a window from which one may perceive all the kingdoms of the earth. . . . Charge your style with life." That is just what he himself was trying to do.The fuzzy instructions set off a huge reaction. "I foresee that 'Young Contributors' will send me worse things than ever now," Higginson boasted to his editor, James T. Fields, whom he wanted to impress. "Two such specimens of verse came yesterday & day before--fortunately not to be forwarded for publication!" But writing to his mother, whom he also wanted to impress, Higginson sounded more sympathetic and humble. "Since that Letter to a Young Contributor I have more wonderful expressions than ever sent me to read with request for advice, which is hard to give."Higginson answered Dickinson right away, asking everything he could think of: the name of her favorite authors, whether she had attended school, if she read Whitman, whether she published, and would she? (Dickinson had not told him that "Safe in their Alabaster Chambers" had appeared in The Republican just six weeks earlier.) Unable to stop himself, he made a few editorial suggestions. "I tried a little,-- a very little--to lead her in the direction of rules and traditions," he later reminisced. She called this practice "surgery.""It was not so painful as I supposed," she wrote on April 25, seeming to welcome his comments. "While my thought is undressed-- I can make the distinction, but when I put them in the Gown--they look alike, and numb." As to his questions, she answered that she had begun writing poetry only very recently. That was untrue. In fact, she dodged several of his queries, Higginson recalled, "with a naive skill such as the most experienced and worldly coquette might envy." She told him she admired Keats, Ruskin, Sir Thomas Browne, and the Brownings, all names Higginson had mentioned in his various essays. Also, the book of Revelation. Yes, she had gone to school "but in your manner of the phrase--had no education." Like him, she responded intensely to nature. Her companions were the nearby Pelham Hills, the sunset, her big dog, Carlo: "they are better than Beings--because they know--but do not tell."What strangeness: a woman of secrets who wanted her secrets kept but wanted you to know she had them. "In a Life that stopped guessing," she once told her sister-in-law, "you and I should not feel at home."Her mother, she confided, "does not care for thought," and although her father has bought her many books, he "begs me not to read them--because he fears they joggle the Mind." She was alone, in other words, and apart. Her family was religious, she continued, "--except me--and address an Eclipse, every morning--whom they call their 'Father.' "She would require a guidance more perspicacious, more concrete.As for her poetry, "I sing, as the Boy does by the Burying Ground--because I am afraid." Such a bald statement would be hard to ignore. "When far afterward--a sudden light on Orchards, or a new fashion in the wind troubled my attention--I felt a palsy, here--the Verses just relieve--."In passing, she dropped an allusion to the two literary editors--she was no novice after all--who "came to my Father's House, this winter--and asked me for my Mind--and when I asked them 'Why,' they said I was penurious--and they, would use it for the World--." It was not worldly approval that she sought; she demanded something different. "I could not weigh myself--Myself," she promptly added, turning slyly to Higginson. This time she signed her letter as "your friend, E-- Dickinson."Bewildered and flattered, he could not help considering that next to such finesse, his tepid tips to a Young Contributor were superfluous. What was an essay, anyway; what, a letter? Her phrases were poems, riddles, lyric apothegms, fleeing with the speed of thought. Her imagination boiled over, spilling onto the page. His did not, no matter how much heat he applied, unless, that is, he lost himself, as he occasionally did in his essays on nature--some are quite magical--or in his writing on behalf of the poor and disenfranchised, when he tackled his subject in clear-eyed prose and did not let it go. Logic and empathy were special gifts. Yet by dispensing pellets of wisdom about how to publish, as he did, in the most prestigious literary journal of the day, he presented himself as a professional man of letters, worth taking seriously, which is just what hehoped to become.This skilled adviser was not as confident as he tried to appear. Perhaps Dickinson sensed this. In the aftermath of Harpers Ferry, Higginson had more or less packed away his revolver and retired to the lakes around his home, where he scoured the woods after the manner of his favorite author, Henry Thoreau. "I cannot think of a bliss as great as to follow the instinct which leads me thither & to wh. I never yet dared fully to trust myself," Higginson confided to his journals. He wrote all the time--about slave uprisings and Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner and also about boating, snowstorms, woodbines, and exercise. Fields printed whatever Higginson gave him and suggested he gather his nature essays into a book.But the Confederates had fired on Fort Sumter, and all bets were off. Then thirty-seven years old (Dickinson was thirty), he unsuccessfully tried to organize a military expedition headed by a son of John Brown's, assuming that the mere sound of Brown's name would wreak havoc in the South. He tried to raise a volunteer regiment in Worcester. That, too, failed. "I have thoroughly made up my mind that my present duty lies at home," he rationalized.By his "present duty" he meant his wife, an invalid who in recent years could not so much as clutch a pen in her gnarled fingers. She needed him. "This war, for which I long and for which I have been training for years, is just as absolutely unobtainable for me as a share in the wars of Napoleon," he confided to his diary. To console himself, he wrote the "Letter to a Young Contributor" in which he declared one need not choose between "a column of newspaper or a column of attack, Wordsworth's 'Lines on Immortality' or Wellington's Lines of Torres Vedras; each is noble, if nobly done, though posterity seems to remember literature the longest." No doubt Dickinson agreed. "The General Rose--decay-- / ," she would write, "But this--in Lady's Drawer / Make Summer--When the Lady lie / In Ceaseless Rosemary--."South Winds jostle them--Bumblebees comeHover--Hesitate--Drink--and are gone--Butterflies pause--on their passage Cashmere--I, softly plucking,Present them--Here--Hover. Hesitate. Drink. Gone: the elusive Dickinson enclosed three more poems in her second letter to Higginson, along with a few pressed flowers. He must have acknowledged the gift quickly, for in early June she wrote him again. "Your letter gave no Drunkenness," she replied, "because I tasted Rum before--Domingo comes but once--yet I have had few pleasures so deep as your opinion."That initial taste of rum had come from an earlier "tutor," who had said he would like to live long enough to see her a poet but then died young. As for Higginson's opinion of her poetry, she took it under ironic advisement. "You think my gait 'spasmodic'--I am in danger--Sir--," she wrote in June as if with a grin. "You think me 'uncontrolled'--I have no Tribunal." To be sure, Higginson could not have been expected to understand all she meant; who could? No matter. She did not enlist him for that, or at least not...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.