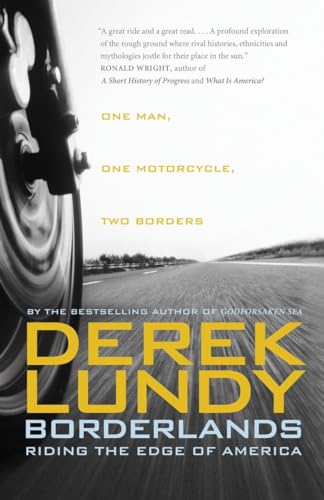

Items related to Borderlands: Riding the Edge of America

"The periphery of a place can tell us a great deal about its heartland. along the edge of a nation's territory, its real prejudices, fears and obsessions - but also its virtues - irrepressibly bubble up as its people confront the 'other' whom they admire, or fear, or hold in contempt, and know little about. September 11, 2001, changed the United States utterly and nothing more so than the physical reality, the perception - and the meaning - of its borders."

-from Borderlands

Derek Lundy turns sixty at the end of a year in which three good friends have died. He feels the need to do something radical, and sets out on his motorcycle - a Kawasaki KLR 650 cc single-cylinder "thumper," which he describes as "unpretentious" and also "butt-ugly." Fascinated by the United States' post-9/11 passion for security, particularly on its two international borders, he chooses to investigate.

He takes a firsthand look at both borders. The U.S.-Mexican borderlands, often disorderly and violent, operate according to their own ad hoc system of rules and conventions, and are distinct in many ways from the two countries the border divides. When security trumps trade, the economic well-being of both countries is threatened, and the upside is difficult to determine. American policy makers think the issues of drugs and illegals are ample reason to keep building fences to keep Mexicans out, even with no evidence that fences work or are anything but cruel. Mexicans' cheap labour keeps the wheels turning in the U.S. economy yet they are resented for trying to get into the country illegally (or legally). More people have died trying to cross this border than in the 9/11 attacks.

At almost 9,000 kilometres, the U.S. border with Canada is the longest in the world. The northern border divides the planet's two biggest trading partners, and that relationship demands the fast, easy flow of goods and services in both directions. Since the events of 9/11, however, the United States has slowly and steadily choked the flux of trade: "just-in-time" parts shipments are in jeopardy; trucks must wait for inspection and clearance; people must be questioned. The border is "thickening."

In prose that is compelling, impressive and at times frightening, Derek Lundy's incredible journey is illuminating enough to change minds, as great writing can sometimes do.

-from Borderlands

Derek Lundy turns sixty at the end of a year in which three good friends have died. He feels the need to do something radical, and sets out on his motorcycle - a Kawasaki KLR 650 cc single-cylinder "thumper," which he describes as "unpretentious" and also "butt-ugly." Fascinated by the United States' post-9/11 passion for security, particularly on its two international borders, he chooses to investigate.

He takes a firsthand look at both borders. The U.S.-Mexican borderlands, often disorderly and violent, operate according to their own ad hoc system of rules and conventions, and are distinct in many ways from the two countries the border divides. When security trumps trade, the economic well-being of both countries is threatened, and the upside is difficult to determine. American policy makers think the issues of drugs and illegals are ample reason to keep building fences to keep Mexicans out, even with no evidence that fences work or are anything but cruel. Mexicans' cheap labour keeps the wheels turning in the U.S. economy yet they are resented for trying to get into the country illegally (or legally). More people have died trying to cross this border than in the 9/11 attacks.

At almost 9,000 kilometres, the U.S. border with Canada is the longest in the world. The northern border divides the planet's two biggest trading partners, and that relationship demands the fast, easy flow of goods and services in both directions. Since the events of 9/11, however, the United States has slowly and steadily choked the flux of trade: "just-in-time" parts shipments are in jeopardy; trucks must wait for inspection and clearance; people must be questioned. The border is "thickening."

In prose that is compelling, impressive and at times frightening, Derek Lundy's incredible journey is illuminating enough to change minds, as great writing can sometimes do.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Derek Lundy is the bestselling author of Godforsaken Sea: Racing The World's Most Dangerous Waters, The Way of a Ship: A Square-Rigger Voyage in the Last Days of Sail, and The Bloody Red Hand: A Journey Through Truth, Myth and Terror in Northern Ireland. He lives and rides on Salt Spring Island, B.C.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

CHAPTER 1

A HOLY ALTAR

THIS LAND IS YOUR LAND, THIS LAND IS MY LAND . . .

THIS LAND WAS MADE FOR YOU AND ME.

—WOODY GUTHRIE

Remember the Alamo? Part of America was forged there. Almost all the elements of America’s story of itself were present during the thirteen-day-long battle in 1836 at a small, remote, old Spanish mission deep in the heart of Texas. I intend to ride the border from east to west, but the Alamo, in the centre of San Antonio, is a necessary place to start. It is about three hundred miles north of Brownsville at the present border’s eastern end, but it’s as much a part of the history of the borderlands as if it was right on the Rio Grande—the River—or in some nearby dusty border town.

Americans remember the story of the Alamo because it seems to represent everything they hold dear in the United States: courage and sacrifice in the name of freedom; like-minded citizens coming together under arms to resist tyranny; a laconic and offhand heroism; an absorption with democracy and the rights of man; a demonstration of America’s destiny to grow west and south, and maybe north, too (perhaps only the ocean could limit this God-sanctioned expansion and dominion). And military prowess: like the soldiers of the War of Independence, the few men at the Alamo fought for a long time against a superior enemy.

The battle at the Alamo was a siege, and it is the sieges of history that catch the imagination: Masada, Constantinople, Londonderry, Leningrad, the Battle of Britain. The besieged almost always have the choice of surrender, a way out of their fear and suffering. They must keep their guts and hearts strong to resist the threat and press of the encircling enemy over a stretch of time. This is far more than the momentary heroism of battle, which rides on a surge of fear and adrenaline, and is over and done with quickly. At four in the morning, in the dark, with time to think about death, how easy and appealing it must seem to get things over with, to give up.

That’s what another group of Americans did a few weeks after the Alamo fell. Between 400 and 450 men under Colonel James Walker Fannin surrendered to the Mexican army under General Antonio López de Santa Anna after the Battle of Coleto Creek, near Goliad, about a hundred miles south of San Antonio. The Americans had been assured of good treatment and they were briefly held prisoner. But on March 27, 1836—Palm Sunday—their guards, under Santa Anna’s orders, and over the objections of less bloody-minded officers, divided them into three groups, marched them off in different directions and massacred them. Three hundred and forty-one men were killed, in an atrocity that mobilized support for the Texan cause across the territory, and within the United States, as well.

Coleto Creek made it clear that this was to be a war to the finish, but somehow it did not trigger a popular emotional response, as did the Alamo. Far more men were killed at Goliad, but unlike the massacre there, the Alamo was a fair fight in the sense that the defenders chose to keep resisting. Killing them was not, therefore, a crime, but merely cruel war.

The account of the Alamo in U.S. mythology is dramatic and colourful. Two hundred men fought to the death against an army of five thousand. It was to be a victory for Protestants over Catholics and for free white men over degenerate mestizos. The American commander, Colonel William B. Travis, traced a line in the sand and said: “Those of you who are willing to stay with me and die with me, cross this line.” All but one man did so. The defenders knew from the beginning that their position was hopeless, but they fought on. Their battle cry was “Victory or Death!” They died to a man on the mission walls and in the shadowy niches of its stone buildings. Davy Crockett was one of them, and his blood, wrote one historian, was shed upon “a holy altar.”

The story has become a part of the mythology of the United States: how it was founded; how it grew and prospered; how it was a beacon for the world it eventually came to dominate. Every nation tells a story of itself to explain and justify how it arrived at where it is now, and to provide guidance and comfort to its people in the present. The myth is the version of itself the nation would like, and in fact needs, to be true.

Historians and other academics revise or debunk myths. They question the story of the Alamo. How can we know what really happened, they churlishly ask, if every man there died? And the fight for Texan independence from Mexico (in 1836, Texas was part of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas) was hardly a battle of cultures. When the Texas Declaration of Independence was signed, David G. Burnet was the president of the new republic, but its vice-president was Lorenzo de Zavala. In those days, a “Texian” was as likely to mean a Spanish-speaking, brown-skinned Catholic whose family had lived in Texas for a hundred years or more, as a white, Protestant Anglo whose parents had recently come from England, Ireland or Germany. But none of these historical nuances or cautions means much to a nation and the story it tells about itself. Historians may quibble, but the people keep the faith.

The chain of events from the Alamo to the border is straightforward. The fight to the death there, and the massacre at Goliad, drew volunteers and aid from the United States. Texas (or the eastern third of the present state north of the Nueces River) won its independence from Mexico with a decisive victory at San Jacinto, later in 1836. Whereas a Texas that was part of a Mexican state could become part of the United States only through invasion and war, an independent Texian republic could join the United States voluntarily. After several unsuccessful attempts (because of disagreements in Congress), the United States annexed a willing Texas in 1845, ignoring Mexico’s loud objections.

For all these reasons of history, I must look at the Alamo if I want to understand the border. I’ll ride to Goliad, too, to find there the antithesis of remembered glory.

Here’s how my motorcycle ride along the two thousand–mile-long U.S.-Mexico border begins: I almost kill myself three, maybe four, times in the first sixty seconds.

In retrospect, this shouldn’t really surprise me. I bought this bike new a few months ago, and I’ve ridden it for about nine hundred miles, none of those in the last six weeks. Before that, I have to go back exactly twenty-five years to the last time I sat on a motorcycle. Now, I’m carrying about ninety pounds of gear on a Kawasaki KLR 650 cc, single-cylinder “thumper,” and it’s the first time I’ve ridden with a heavy load of any sort. I’m wearing my brand new armoured riding jacket, pants and boots—the first time I’ve worn them all together—and their padded bulk distracts me. Protecting my precious skull is a new helmet, different in design from the one I’m somewhat used to. It’s a “full coverage” helmet with a chin guard as well as a plastic visor, and it feels claustrophobic.

I have to pull out of a motel parking lot onto the service road of Interstate 10 on the fringe of San Antonio, Texas; the traffic, even on this road, is moving at forty or fifty miles an hour. I must turn into the fast-moving stream, accelerate hard, crunch my way through the gears, and, as I’m doing that, merge left across three lanes to get onto the highway itself. If I wanted to attempt suicide on a motorcycle, this would be a pretty good way to do it.

I wait for a hole in the rush of heavy metal, turn out of the driveway, and twist the throttle. Right away, it’s time to change into second. I have to slide my left foot under the shift lever, but I can’t do it. The armoured pads in my pants make it difficult to bend my knee, which also butts up against the pannier bag hanging down over the gas tank in front of me. I can’t manoeuvre my leg to get my foot into position. It just never occurred to me to check beforehand that I could do this. Cars scream and screech around me, braking hard, swerving; I’m going way too slowly. In my rear-view mirror, I see a jagged wall of vehicles bearing down on me; they look like squadrons of tanks. In a few seconds, I pass from worry to fear to sweaty terror. I’ve already begun to change lanes; now I reef the bike back to the right, trying to avoid getting sucked onto the highway at twenty miles an hour. The bike’s engine is screaming in first gear; if I were in fifth, I’d be hammering along at fifty miles an hour. Then . . . there . . . did it—into second gear. I twist the throttle. I throttle it. I signal left again, but then, the same problem: I can’t get into third. I slide back to the right again.

In all these changes of direction, I’m aware of large metal masses flashing by me on both sides, very close. Horns honk in a weird doppler rise and fall—a reflection of how fast the other vehicles are, how slow I am. Someone shouts at me: “Asshole!” He’s right. I feel what I’m sure is the slight “thlip” of a car’s outside mirror flicking the arm of my jacket as it zips by—another two inches and it could have ripped off my goddamn arm. Holy fucking shit! Dear God, nearer to thee: I renounce atheism. This is madness; I’m going to die. I feel the deep sorrow the prematurely dying feel for the people they’re about to leave behind; for my wife, and for my daughter and her teenage orphanhood.

But then a side road appears on the right. I slam the bike into it too fast, and the rear wheel slides; I wobble, unused to the feel of the luggage-loaded machine. Just managing to stay upright, I pull over to the road’s quiet edge. I put my boots down, and sit in the saddle. I shake, I almost puke, in the aftershock of my barely avoided death.

Thoughts pass at random through my alleged mind: I’m so stupid . . . no, I’m a colossal idiot; I’m too old for this; I’ll never make it to the goddamn border, never mind ride its long length, on bad roads, with bad guys all around; what in the name of sweet Jesus do I think I’m doing? Why the hell didn’t I check that I could actually ride this bike with a big load and my unfamiliar riding gear, before inserting myself into heavy traffic? I damn near joined you then, boys, I say to Will, Chris and Mike.

I prop the bike on its side stand and dismount. My legs feel fragile, not quite attached to my torso. I wonder vaguely what my blood pressure was a few minutes ago out there on the road. High, very high. It won’t be the last time it red-lines on this trip, I’m sure of that. I’m old enough that this is something I think about.

I reposition the tank panniers so that I have more knee room, but it’s not a perfect adjustment for my long legs and feet. Sitting in the saddle again, I can get my toe under the shift lever only if I bend my leg out from the bike at an odd angle. I ride up and down the quiet, dead-end side road trying out my technique. It works most of the time, although I often miss the gear, and sometimes I have to look down to make sure my foot is in the right position before I flip up the lever. Taking your eyes off the road’s variegated surface, and away from the close surround of traffic is not at all a safe practice on a two-wheeler. But my adaptation will have to do, and I hope I’ll get used to it.

The second beginning of my border ride works well enough. I reach the highway in jerky, knees-akimbo manoeuvres. I’m glad there are no veteran bikers around judging my greenhorn style as I jam the lever into top gear and reach a cruising speed of sixty or sixty-five miles an hour—without risking my life more than is usual for a ride in foreign, city-expressway traffic. At least I planned ahead enough to avoid rush hour; it’s around eleven o’clock and there’s a medium amount of traffic about. I must have made an even distribution of my load because, once I settle down in my lane, in the flow of vehicles, the bike feels balanced and, even with the added weight, there’s no lessening of power I’m aware of.

In spite of my very bad start, my discomfort is displaced right away by a surge of pure motorcycle happiness. It’s an emotional summary of all the constituents of riding fast: in the open, in the rush of wind, under the wide sky, with the road sweeping by below, everything around brought into insistent and immediate focus. It’s the happiness of adrenaline and the abandonment of constraints—with an edge of danger. When you’re sitting around and talking about riding, it’s easy to acknowledge the possibilities of disaster, but once on the bike, on the road, all those intimations of mortality are swept full away by joy.

I begin my first day by riding away from the Alamo, north and east towards Austin to meet a friend. Jane was a business associate, ex-campaign manager and old friend of Ann Richards, the Democratic governor of Texas whom George W. Bush defeated in his stroll to the presidency. By some unlikely coincidence, Jane lives part of the year on Salt Spring Island, my own small, remote home off the coast of British Columbia.

I head north out of San Antonio, away from the traffic and congestion, and into the low hills, sandy plains and trees—cottonwood, willow and acacia—of this eastern edge of the Texas Hill Country. On this less-travelled road, there are few small towns—Twin Sisters, Blanco, Dripping Springs—and, therefore, only a few gear changes. This is nice, but I’m not getting much practice. As I ride, the weather grows cooler and cloudier. It looks like rain, which is just what I don’t need on my first traumatic day, but it holds off. The wind is a problem, though. It blows across my path or dead against me, depending on the road’s curves. It’s confirmation that this bike doesn’t do well in a crosswind; even a gust at twenty miles an hour blows me around my lane. I’m beginning my battle with the wind, which will continue, most days, for the next four weeks. Twice, it will come close to killing me.

I sit on the curb outside a gas-station store eating a ready-made ham and cheese sandwich on white and a Snickers bar, drinking a coffee. While I eat, I admire my motorcycle. Or rather, I try, once again, to justify—and to appreciate—its ungainliness. The KLR 650’s tall, somewhat broken-backed profile, high fenders and hand guards make the bike look like a large, steroid-pumped dirt bike. It is to other motorcycles as the head-hunched stork is to birds, the humpback to whales, the hyena to land mammals. With the stock nubby tires (I’ve changed to more street-kindly rubber for this trip), it can go off-road under a skilled rider, but it’s too heavy a machine to do much of that.

The KLR’s real appeal is not that it’s born to do one thing well, but that it can do several disparate things reasonably well. For example, a sleek, chromed Harley-Davidson can hum along a good road, at speed, in comfort, but it gets into trouble when the road surface turns bad. The KLR can bash over ugly, rocky gravel and dirt roads, and, if necessary, go where there isn’t a road; pound along the freeway all day at seventy or seventy-five miles an hour—not in real comfort, but it can do it; carry more fuel than most other mot...

A HOLY ALTAR

THIS LAND IS YOUR LAND, THIS LAND IS MY LAND . . .

THIS LAND WAS MADE FOR YOU AND ME.

—WOODY GUTHRIE

Remember the Alamo? Part of America was forged there. Almost all the elements of America’s story of itself were present during the thirteen-day-long battle in 1836 at a small, remote, old Spanish mission deep in the heart of Texas. I intend to ride the border from east to west, but the Alamo, in the centre of San Antonio, is a necessary place to start. It is about three hundred miles north of Brownsville at the present border’s eastern end, but it’s as much a part of the history of the borderlands as if it was right on the Rio Grande—the River—or in some nearby dusty border town.

Americans remember the story of the Alamo because it seems to represent everything they hold dear in the United States: courage and sacrifice in the name of freedom; like-minded citizens coming together under arms to resist tyranny; a laconic and offhand heroism; an absorption with democracy and the rights of man; a demonstration of America’s destiny to grow west and south, and maybe north, too (perhaps only the ocean could limit this God-sanctioned expansion and dominion). And military prowess: like the soldiers of the War of Independence, the few men at the Alamo fought for a long time against a superior enemy.

The battle at the Alamo was a siege, and it is the sieges of history that catch the imagination: Masada, Constantinople, Londonderry, Leningrad, the Battle of Britain. The besieged almost always have the choice of surrender, a way out of their fear and suffering. They must keep their guts and hearts strong to resist the threat and press of the encircling enemy over a stretch of time. This is far more than the momentary heroism of battle, which rides on a surge of fear and adrenaline, and is over and done with quickly. At four in the morning, in the dark, with time to think about death, how easy and appealing it must seem to get things over with, to give up.

That’s what another group of Americans did a few weeks after the Alamo fell. Between 400 and 450 men under Colonel James Walker Fannin surrendered to the Mexican army under General Antonio López de Santa Anna after the Battle of Coleto Creek, near Goliad, about a hundred miles south of San Antonio. The Americans had been assured of good treatment and they were briefly held prisoner. But on March 27, 1836—Palm Sunday—their guards, under Santa Anna’s orders, and over the objections of less bloody-minded officers, divided them into three groups, marched them off in different directions and massacred them. Three hundred and forty-one men were killed, in an atrocity that mobilized support for the Texan cause across the territory, and within the United States, as well.

Coleto Creek made it clear that this was to be a war to the finish, but somehow it did not trigger a popular emotional response, as did the Alamo. Far more men were killed at Goliad, but unlike the massacre there, the Alamo was a fair fight in the sense that the defenders chose to keep resisting. Killing them was not, therefore, a crime, but merely cruel war.

The account of the Alamo in U.S. mythology is dramatic and colourful. Two hundred men fought to the death against an army of five thousand. It was to be a victory for Protestants over Catholics and for free white men over degenerate mestizos. The American commander, Colonel William B. Travis, traced a line in the sand and said: “Those of you who are willing to stay with me and die with me, cross this line.” All but one man did so. The defenders knew from the beginning that their position was hopeless, but they fought on. Their battle cry was “Victory or Death!” They died to a man on the mission walls and in the shadowy niches of its stone buildings. Davy Crockett was one of them, and his blood, wrote one historian, was shed upon “a holy altar.”

The story has become a part of the mythology of the United States: how it was founded; how it grew and prospered; how it was a beacon for the world it eventually came to dominate. Every nation tells a story of itself to explain and justify how it arrived at where it is now, and to provide guidance and comfort to its people in the present. The myth is the version of itself the nation would like, and in fact needs, to be true.

Historians and other academics revise or debunk myths. They question the story of the Alamo. How can we know what really happened, they churlishly ask, if every man there died? And the fight for Texan independence from Mexico (in 1836, Texas was part of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas) was hardly a battle of cultures. When the Texas Declaration of Independence was signed, David G. Burnet was the president of the new republic, but its vice-president was Lorenzo de Zavala. In those days, a “Texian” was as likely to mean a Spanish-speaking, brown-skinned Catholic whose family had lived in Texas for a hundred years or more, as a white, Protestant Anglo whose parents had recently come from England, Ireland or Germany. But none of these historical nuances or cautions means much to a nation and the story it tells about itself. Historians may quibble, but the people keep the faith.

The chain of events from the Alamo to the border is straightforward. The fight to the death there, and the massacre at Goliad, drew volunteers and aid from the United States. Texas (or the eastern third of the present state north of the Nueces River) won its independence from Mexico with a decisive victory at San Jacinto, later in 1836. Whereas a Texas that was part of a Mexican state could become part of the United States only through invasion and war, an independent Texian republic could join the United States voluntarily. After several unsuccessful attempts (because of disagreements in Congress), the United States annexed a willing Texas in 1845, ignoring Mexico’s loud objections.

For all these reasons of history, I must look at the Alamo if I want to understand the border. I’ll ride to Goliad, too, to find there the antithesis of remembered glory.

Here’s how my motorcycle ride along the two thousand–mile-long U.S.-Mexico border begins: I almost kill myself three, maybe four, times in the first sixty seconds.

In retrospect, this shouldn’t really surprise me. I bought this bike new a few months ago, and I’ve ridden it for about nine hundred miles, none of those in the last six weeks. Before that, I have to go back exactly twenty-five years to the last time I sat on a motorcycle. Now, I’m carrying about ninety pounds of gear on a Kawasaki KLR 650 cc, single-cylinder “thumper,” and it’s the first time I’ve ridden with a heavy load of any sort. I’m wearing my brand new armoured riding jacket, pants and boots—the first time I’ve worn them all together—and their padded bulk distracts me. Protecting my precious skull is a new helmet, different in design from the one I’m somewhat used to. It’s a “full coverage” helmet with a chin guard as well as a plastic visor, and it feels claustrophobic.

I have to pull out of a motel parking lot onto the service road of Interstate 10 on the fringe of San Antonio, Texas; the traffic, even on this road, is moving at forty or fifty miles an hour. I must turn into the fast-moving stream, accelerate hard, crunch my way through the gears, and, as I’m doing that, merge left across three lanes to get onto the highway itself. If I wanted to attempt suicide on a motorcycle, this would be a pretty good way to do it.

I wait for a hole in the rush of heavy metal, turn out of the driveway, and twist the throttle. Right away, it’s time to change into second. I have to slide my left foot under the shift lever, but I can’t do it. The armoured pads in my pants make it difficult to bend my knee, which also butts up against the pannier bag hanging down over the gas tank in front of me. I can’t manoeuvre my leg to get my foot into position. It just never occurred to me to check beforehand that I could do this. Cars scream and screech around me, braking hard, swerving; I’m going way too slowly. In my rear-view mirror, I see a jagged wall of vehicles bearing down on me; they look like squadrons of tanks. In a few seconds, I pass from worry to fear to sweaty terror. I’ve already begun to change lanes; now I reef the bike back to the right, trying to avoid getting sucked onto the highway at twenty miles an hour. The bike’s engine is screaming in first gear; if I were in fifth, I’d be hammering along at fifty miles an hour. Then . . . there . . . did it—into second gear. I twist the throttle. I throttle it. I signal left again, but then, the same problem: I can’t get into third. I slide back to the right again.

In all these changes of direction, I’m aware of large metal masses flashing by me on both sides, very close. Horns honk in a weird doppler rise and fall—a reflection of how fast the other vehicles are, how slow I am. Someone shouts at me: “Asshole!” He’s right. I feel what I’m sure is the slight “thlip” of a car’s outside mirror flicking the arm of my jacket as it zips by—another two inches and it could have ripped off my goddamn arm. Holy fucking shit! Dear God, nearer to thee: I renounce atheism. This is madness; I’m going to die. I feel the deep sorrow the prematurely dying feel for the people they’re about to leave behind; for my wife, and for my daughter and her teenage orphanhood.

But then a side road appears on the right. I slam the bike into it too fast, and the rear wheel slides; I wobble, unused to the feel of the luggage-loaded machine. Just managing to stay upright, I pull over to the road’s quiet edge. I put my boots down, and sit in the saddle. I shake, I almost puke, in the aftershock of my barely avoided death.

Thoughts pass at random through my alleged mind: I’m so stupid . . . no, I’m a colossal idiot; I’m too old for this; I’ll never make it to the goddamn border, never mind ride its long length, on bad roads, with bad guys all around; what in the name of sweet Jesus do I think I’m doing? Why the hell didn’t I check that I could actually ride this bike with a big load and my unfamiliar riding gear, before inserting myself into heavy traffic? I damn near joined you then, boys, I say to Will, Chris and Mike.

I prop the bike on its side stand and dismount. My legs feel fragile, not quite attached to my torso. I wonder vaguely what my blood pressure was a few minutes ago out there on the road. High, very high. It won’t be the last time it red-lines on this trip, I’m sure of that. I’m old enough that this is something I think about.

I reposition the tank panniers so that I have more knee room, but it’s not a perfect adjustment for my long legs and feet. Sitting in the saddle again, I can get my toe under the shift lever only if I bend my leg out from the bike at an odd angle. I ride up and down the quiet, dead-end side road trying out my technique. It works most of the time, although I often miss the gear, and sometimes I have to look down to make sure my foot is in the right position before I flip up the lever. Taking your eyes off the road’s variegated surface, and away from the close surround of traffic is not at all a safe practice on a two-wheeler. But my adaptation will have to do, and I hope I’ll get used to it.

The second beginning of my border ride works well enough. I reach the highway in jerky, knees-akimbo manoeuvres. I’m glad there are no veteran bikers around judging my greenhorn style as I jam the lever into top gear and reach a cruising speed of sixty or sixty-five miles an hour—without risking my life more than is usual for a ride in foreign, city-expressway traffic. At least I planned ahead enough to avoid rush hour; it’s around eleven o’clock and there’s a medium amount of traffic about. I must have made an even distribution of my load because, once I settle down in my lane, in the flow of vehicles, the bike feels balanced and, even with the added weight, there’s no lessening of power I’m aware of.

In spite of my very bad start, my discomfort is displaced right away by a surge of pure motorcycle happiness. It’s an emotional summary of all the constituents of riding fast: in the open, in the rush of wind, under the wide sky, with the road sweeping by below, everything around brought into insistent and immediate focus. It’s the happiness of adrenaline and the abandonment of constraints—with an edge of danger. When you’re sitting around and talking about riding, it’s easy to acknowledge the possibilities of disaster, but once on the bike, on the road, all those intimations of mortality are swept full away by joy.

I begin my first day by riding away from the Alamo, north and east towards Austin to meet a friend. Jane was a business associate, ex-campaign manager and old friend of Ann Richards, the Democratic governor of Texas whom George W. Bush defeated in his stroll to the presidency. By some unlikely coincidence, Jane lives part of the year on Salt Spring Island, my own small, remote home off the coast of British Columbia.

I head north out of San Antonio, away from the traffic and congestion, and into the low hills, sandy plains and trees—cottonwood, willow and acacia—of this eastern edge of the Texas Hill Country. On this less-travelled road, there are few small towns—Twin Sisters, Blanco, Dripping Springs—and, therefore, only a few gear changes. This is nice, but I’m not getting much practice. As I ride, the weather grows cooler and cloudier. It looks like rain, which is just what I don’t need on my first traumatic day, but it holds off. The wind is a problem, though. It blows across my path or dead against me, depending on the road’s curves. It’s confirmation that this bike doesn’t do well in a crosswind; even a gust at twenty miles an hour blows me around my lane. I’m beginning my battle with the wind, which will continue, most days, for the next four weeks. Twice, it will come close to killing me.

I sit on the curb outside a gas-station store eating a ready-made ham and cheese sandwich on white and a Snickers bar, drinking a coffee. While I eat, I admire my motorcycle. Or rather, I try, once again, to justify—and to appreciate—its ungainliness. The KLR 650’s tall, somewhat broken-backed profile, high fenders and hand guards make the bike look like a large, steroid-pumped dirt bike. It is to other motorcycles as the head-hunched stork is to birds, the humpback to whales, the hyena to land mammals. With the stock nubby tires (I’ve changed to more street-kindly rubber for this trip), it can go off-road under a skilled rider, but it’s too heavy a machine to do much of that.

The KLR’s real appeal is not that it’s born to do one thing well, but that it can do several disparate things reasonably well. For example, a sleek, chromed Harley-Davidson can hum along a good road, at speed, in comfort, but it gets into trouble when the road surface turns bad. The KLR can bash over ugly, rocky gravel and dirt roads, and, if necessary, go where there isn’t a road; pound along the freeway all day at seventy or seventy-five miles an hour—not in real comfort, but it can do it; carry more fuel than most other mot...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherVintage Canada

- Publication date2011

- ISBN 10 0307398633

- ISBN 13 9780307398635

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages432

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 82.63

Shipping:

US$ 4.13

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

BORDERLANDS: RIDING THE EDGE OF

Published by

Vintage Canada

(2011)

ISBN 10: 0307398633

ISBN 13: 9780307398635

New

Softcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.69. Seller Inventory # Q-0307398633

Buy New

US$ 82.63

Convert currency