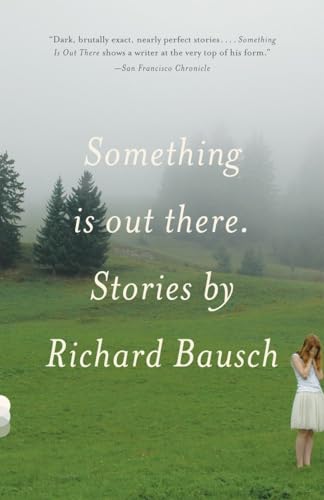

Items related to Something Is Out There: Stories (Vintage Contemporaries)

In these eleven unforgettable stories, Richard Bausch plumbs the depths of familial and marital estrangement, the gulfs between friends and lovers, the fragility and impermanence of love—and manages to find something quite surprising: human hope.

Bausch’s assured style, signature grace, and penetrating wit shine on every page, confirming his stature as one of America’s most beloved and acclaimed writers.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Richard Bausch is the author of seven previous volumes of short stories and eleven novels. He is the recipient of an award in literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Lila Wallace–Reader’s Digest Writers’ Award, the PEN/Malamud Award for Short Fiction, and, for his novel Peace, the American Library Association’s W. Y. Boyd Prize for Excellence in Military Fiction and the Dayton Literary Peace Prize. A past chancellor of the Fellowship of Southern Writers, he lives in Memphis, Tennessee, where he holds the Moss Chair of Excellence in the Writers Workshop of the University of Memphis.

The middle of spring in Memphis and it felt like winter. Tonight, setting out the recycling, she got a chill and it took a good ten minutes to get rid of it. She had him hold her, and breathe warm at her neck. They lay in the bed under the ceiling light, because he said it would feel like warmth shining down on them. She thought of the waste of electricity. “Can you turn it off?” she said.

“I’m cold, too.”

“Please?”

“You turn it off.”

She was quiet. In a little while he got up and flicked the switch and then crawled in at her back, shivering. “I’d like to turn the heat on.”

“Stay,” she said.

“I’m dying.”

“We’ll be warm now.”

“It’s too bloody cold.”

“Don’t go, please.”

He lay there shivering, and she reached back to pull him closer. The cold air of the room seemed to be flowing in at his neck, so he pulled the blanket higher, burrowing in, breathing his own exhalation for the warmth. It wasn’t enough. He would never sleep like this, with the chill in his bones, and he wanted to be rested.

They had an appointment early the next day with the Immigration Office to prove that they were a real married couple. They had been married a year now, and his student visa was no longer valid; he would have to get a permanent residency card in order to work. He was from Ireland. Belfast. His parents still lived there. An elderly sullen couple whose exhaustive politeness to her, during her one visit to their house, seemed tinged with a kind of pity, as though they deplored her exposure to them; there was no other way to parse it. And the way they were together made it easy enough to believe. They barely spoke. Michael said they had been that way as long as he could remember, and not to worry about it. But she couldn’t help feeling sorry for having disturbed their stolid existence in the green countryside.

While he finished his degree in history, she had supported him with her teaching job at the Memphis College of Art. She took the job at the end of their first year together, after a period that she considered spendthrift. They had spent a lot of money traveling around, and he was now past thirty, and things were tight. The economy was in the tank, and the administrators at the college were talking about furloughs— the delicate word in the academy for layoffs. He was going to have to find work.

He was ready. There was a need for history teachers at the high school. He had completed his degree, and written his thesis and defended it, and the book was in its tight green binding in the big long shelf of them in the university library. The thesis was about the Kennedy years, especially the problem of Berlin, and the Wall. He knew all about the cold war, and for many nights now in this winter and early spring he had been joking with her about this cold war, the trying to sleep while something is out there their teeth chattered and their muscles shook, and she claimed she liked a cold room and a warm bed, and of course it was nothing of the kind; it was her confounded fear of spending money. In the summer, she would insist that seventy degrees was too cold, and in blazing hot and thickly humid Memphis, she required that the thermostat be set at seventy- five degrees. They argued, back and forth. He made jokes about it in company. She swore that sixty- eight degrees in winter was different than sixty- eight degrees in summer.

He said, “Sure and you get the place down to thirty- two degrees Fahrenheit on any day of the year, summer fall winter spring, and the water’ll freeze.”

“It just feels different,” she said.

“Either way, at thirty- two degrees, the water freezes and we die of exposure.”

Now he waited for her to go to sleep, so he could get up and put the heat on. But she lay there shivering and murmuring about the things they would need in the morning for the meeting with the Immigration people.

He didn’t want to talk about it. And even with the shaking he was beginning to be sleepy.

“The marriage license,” she said. “Did we put that in?”

“Did you? Because I don’t remember seeing it.”

“The marriage license is the most important thing.”

“I’ll look in the morning.”

“Can you check it now?”

“If you want to check it, love, you go right ahead.”

She sighed again but did not move.

He sought to remember if he had seen the marriage license. There was too much to think about. He moved a little, and sighed, and shook.

She said, “Good night.”

“I can’t sleep. This is fucking daft. We might as well be in the Arctic.”

She was silent. One of the things she found a bit taxing about him at times was his ability to concentrate on his own distress in any situation. He could be eloquent about it, spending energy delineating all the facets of whatever trouble had arisen, often enough trouble he had brought upon himself. She had never known a more disorganized man, and his lack of any kind of practical skill had worn her out during the process of gathering all that they would need for the morning’s meeting: birth records and school transcripts, tax forms, proof of themselves as they were. The marriage license. She loved him, loved his humor and his voice and his soft brogue, but she was also exasperated by him.

“I’m worried about the pictures, too,” she said to him now.

“We don’t have enough pictures, do we?”

“You want to get up and take a few more?”

“No. And stop it.”

“I think we should bring stool samples,” he said, sounding serious.

She didn’t answer, but turned, facing him, and put her cupped hands to her mouth and breathed the warmth. “I won’t be able to sleep if I don’t know the marriage license is in there.”

“Did you put it in there?” he said.

“I don’t remember.”

“Good night, Rita. We’ll check it in the morning.”

In the middle of the night, she awoke, sweating, and sat up, worried about the time. He was sprawled on his side, legs out of the blankets. She got up and went into the hall and flicked the light switch. He had turned the heat on in the night— probably while half- asleep. She turned it off and went into the kitchen. All the documents were arrayed on the table, with the two books of photographs: the many images of that busy first year. She looked through them again. Here were the two of them together and apart in many happy poses. The books were labeled WORLD TRAVELERS: him smiling clownishly on a sunny street near the Spanish Steps in Rome; the two of them embracing on the flat dirt lawn of a chateau in the Loire Valley; him seated at a café table outside a small village in Normandy, with bread and cheese and pretty shining bottles of red wine before him, and then her in the same pose, at the same table; both of them lounging and being silly in front of a pension in Paris, a gloomy- looking ivy wall and narrow windows behind them; and here were several from the rainy afternoon in Belfast at his parents’ cottage with its heavy stone entrance and its low ceilings. And there were the ones from the year before, both of them by the fish market at San Francisco Bay, with Alcatraz brooding behind them in a cowl of drifting fog. And then there were several of them with her parents— who, last year, had divorced after thirty years— and her brothers and sisters in Virginia, everyone smiling into the camera, a sunny cool day in Fredericksburg, and he had said, when she showed it to him, “Ah, here we all are in happier times.”

“What does that mean?” she said. “Are you talking about my mother and dad?”

“I have the thought any time I look at a picture like that, no matter who’s in it.”

“Well, everyone’s here. Including you.”

“Don’t rile yourself, darlin’. It’s a general thought I have every time I look at such a photograph, since I was a little tyke. ‘Here we are in happier times.’ And tell me straight from your heart, isn’t that the truth of it?”

Now she closed the photo books and put them in the folderwith the other papers. She supposed this would be enough. She worried about it all, nevertheless. The forms had been so daunting. And she remembered now that all the travel had been strenuous and had taken a toll on her nerves. In several of the pictures she looked carefree and glad, and she could recall the sense that it was something she put on, a ruse, to hide the stress of worrying about the money and the next flight.

Indeed, he would say that the strain she felt wasn’t the travel but spending the money. And they had spent it, too, all of it— fifteen thousand dollars of an inheritance from his great uncle, who had made a fortune in the coal business and then lost most of it, and then made a lot back selling stocks. He left each of his surviving nephew’s children a single flat payment calculated from an obscure formula he had devised that had to do with time spent in his company. Michael had lived in the old man’s house one summer in Donegal before he started college. He often talked about him as a kind of natural force, a man who could be singularly unpleasant to be around, so strange and unpredictable, even volatile, but in the end hugely interesting: after you had been with him you realized that you hadn’t been slightly bored. And he paid attention— the behest to Michael was accompanied by a note telling him that he should use it to study history. Michael was nearing completion of his degree at the time, and the advice seemed prescient.

Well, and a man who travels the world is in his way also studying the past.

He woke alone in the bed, turned, and looked at the faint outline of the door. He pulled the blanket up, knowing that she would’ve turned off the heat. Lying awake, he went over the arguments for sixty- eight degrees in the winter and seventy- five degrees in the summer. The whole thing was a perfect illustration of the economic anxiety of the lower middle classes. The phrase came to him like a quip he might use, but then he thought of her face, the sweet oval of it, and these little peccadilloes of hers were funny if you didn’t let them annoy you.

He turned over again, wondering at the time and deciding that she must be seeking to reassure herself about all the materials they had gathered for tomorrow. Probably she had already located the marriage license, and probably it had been packed early, among the first things they thought about. How upsetting it was to think that you were going to be subject to the whims of the national government as manifested in the person of a single clerk— somebody working a job, with a desk and a computer and photographs of his family on the desk, and posters and paintings on his office wall. Michael pictured himself and Rita seated across a gray desk, with their lives before them in the envelopes and folders, while this little imagined balding gloomy man combed through everything, making little check marks on a legal pad as he went along. Perhaps he had lapsed into a dream, because her movement in the room startled him. She got into the bed very carefully, and lay with her back to him.

“Did we pack it?” he said.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to wake you.”

“Did you find it?”

“It’s there. You must’ve packed it.”

“Well, if I did I don’t remember it.”

She closed her eyes and tried to drift off. He lay still, as if listening for her. She murmured, “Michael?”

Nothing.

It was a long night. She kept waking up, and she had a consecutive- feeling dream, a senseless narrative that kept unwinding. When light came to the window she gingerly removed herself from the bed, and put her robe on. In the hallway she checked the thermostat. Sixty- five degrees. She looked out the window at the street, with its shade trees and flowers. It was a bright morning, and dew was on the grass, sparkles everywhere, and the shade was dark blue. A beautiful day, cool and breezy, without a cloud in the sky. She put coffee on and sat by the front window taking it all in. She saw the neighbors come out and get in their van and drive away. Another neighbor, a woman she had only waved to now and then, came along the sidewalk with a big white dog on a leash, being pulled by him. She wore overalls over a white T- shirt and looked out of sorts. Rita laid her head on the back of the chair and closed her eyes.

And fell asleep.

He woke to the sound of her cell phone alarm, and said sleepily, “Turn it off, sweetie, please?”

When she gave no answer he said in a pleading and frustrated tone, nearly a whine: “Oh, come onnnn. I’m up. Turn it off.” He opened his eyes, and saw that she wasn’t there. So she was up and getting ready. “Good,” he murmured aloud. And he turned the phone off and lay back down. He would wait until she came to wake him. He, too, fell asleep.

The INS office in Memphis is on Summer Avenue. Summer is a long street. It runs west all the way to Parkway North and the river, and to the east it goes all the way to Lakeland, and beyond. They both knew the street without being able to tell from the number exactly where the office might be. Their appointment was for eight- thirty a.m.

He woke just before eight o’clock. He got out of the bed and went into the bathroom and looked at himself in the mirror. Then he looked at the clock on the wall to his left.

Rita woke to the sound of him moving through the house. They hurried into their clothes, barely speaking, and by eight-sixteen they were in the car, with him driving, speeding toward Highway 240, which was the shortest way to Summer. Neither of them spoke. They didn’t know which way to turn on Summer. He thought she had looked it up, and she thought he had.

“It’s your responsibility,” she told him. “I thought you’d do it.”

“Call them,” he said. “Can you do that?”

“Why didn’t you get up with the alarm?”

“I thought you were up. You were up.”

“I had a bad night. I couldn’t sleep. Christ. Sue me.”

“Where were you?”

“I fell asleep in the chair.”

“Call them. We’re almost to the exit.”

She keyed in the number, and got a recording, with choices. She had to scroll through them. He pulled over on the cloverleaf that would take them down to the light at Summer. Right would be west, left would be east.

She keyed angrily— sighing with exasperation and muttering under her breath— through the choices. And finally she was speaking to someone. He looked out at the highway and the parking lot of Garden Ridge Home Store, the drive- in theater screen beyond. The appointment form stated unequivocally that if a petitioner was late, the appointment would be canceled and all forms would become invalid. The entire process of seeking the card would have to be repeated. He tapped the wheel, listening to her.

She said, “We’re at the 240 interchange. The light there.”

“Take a left at the light,” said the voice on the telephone, “And then take the first right and go to the end of the drive. We’re right there.”

“Thank you,” Rita said. She snapped the phone shut. “We’re in luck.”

“I heard.” He was already pulling the car out, but the blare of a truck horn stopped him. He slammed on the brake and she pitched forward. The folders on her lap fell to the floor at her feet.

He watched the truck, a big semi- trailer, go on past, down to the light. He looked back and carefully pulled out. He knew she was displeased with him. She hadn’t reached to retrieve the folders.

“You’re the one that fell asleep in the chair.”

“It’s your permanent residency. You’d think that would make you a little concerned for the details— like where the office is.”

“We’re in luck,” he said. “Remember?”

The sound that came from her was not a word.

“C...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherVintage

- Publication date2011

- ISBN 10 0307279146

- ISBN 13 9780307279149

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Something Is Out There: Stories (Vintage Contemporaries)

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 52GZZZ00WMDX_ns

SOMETHING IS OUT THERE: STORIES

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.66. Seller Inventory # Q-0307279146